(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

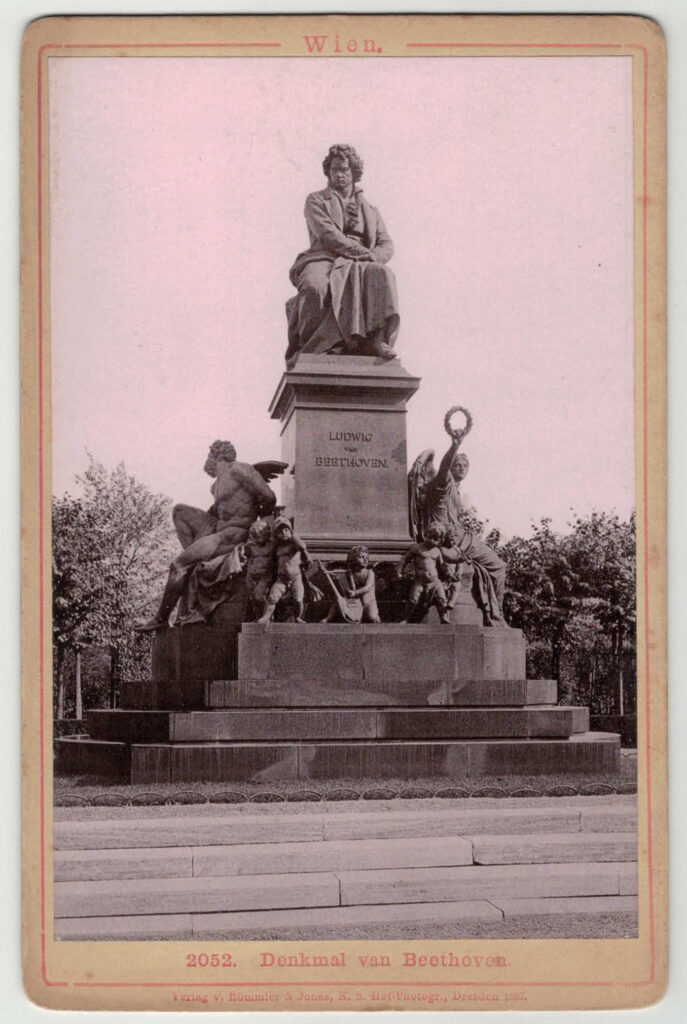

(Verlag v. Römmler & Jonas, K.S. Hof-Photogr., Dresden; from the collection of William Meredith). For an illustration of the dedication, see: https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=niz&datum=18800509&seite=8&zoom=33

(Photo credit: William Meredith) To see Zumbusch’s sketch for the monument, see https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=niz&datum=18740308&seite=3&zoom=33

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

![Postcard of a drawing for a painting by Schulz-Curtius with an inscription on the front: "The most lifelike picture of Beethoven known to me, Eduard Hummel [1814-1892], son of J. Nep. Hummel [and Elisabeth (Betty) Röckel Hummel]), who saw the composer before his death. Wiesbaden. 1878." Eduard was 13 when Beethoven died. Betty Hummel's lock of Beethoven's hair is at the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies at SJSU in a frame with a lock of Goethe's hair, Beethoven's last quill pen, and locks of hair from her family and royalty.](https://beethovenscholar.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Eduard-Hummel-front-pdf-1.jpg)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

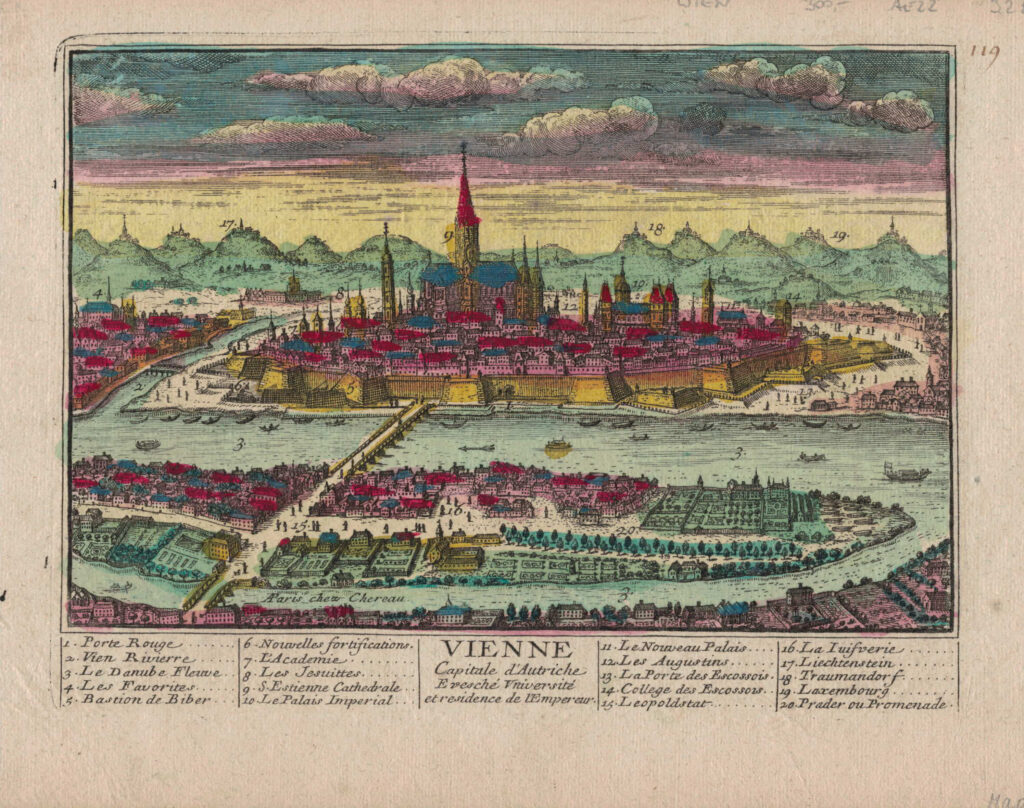

(originally colored engraving by Chereau, Parism ca. 1770; from the collection of William Meredith)

(The other greatest monument is also in Vienna: Klimt’s “Beethoven Frieze.”)

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(Photo credit: William Meredith) For illustrations of Nike, Prometheus, and the putti, see https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=niz&datum=18800509&seite=9&zoom=33

object/G_1816-0610-501

(Photo credit: William Meredith)

(“Resounding symphony, ‘Freude, schöner Götterfunken,’ the swansong.” See: http://www.lvbeethoven.com/Bio/BiographyFuneralOration.html )

(Photo credit: William Meredith)