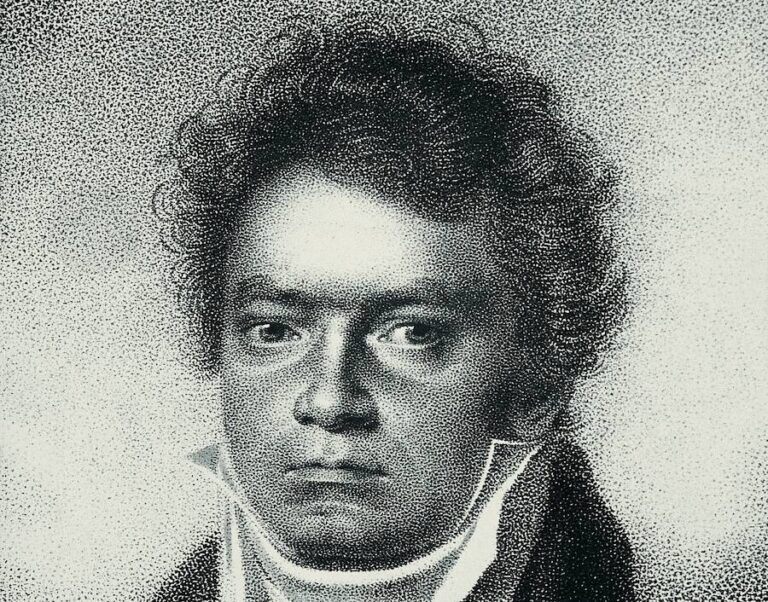

What the Genome Tells Us and A Brief Review of the History of the Question.

For the past four decades, one of the most intensely debated issues in popular culture about Beethoven was whether or not the composer was either Moorish or black. The question was first raised more than a century ago by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, addressed more significantly in the 1940s by Joel A. Rogers, and resurfaced in the black power movement of the 1960s and 70s and in the “Black Lives Matter” movement of the last decade. Though mostly ignored by most Beethoven biographers (excluding, that is, the influential Alexander Wheelock Thayer), the history of the question is important even though, because of the publication of the first research paper on Beethoven’s genome in 2023, we now know the answer to the composer’s ancestry.

In late 2022 I asked the principal author of the genome paper, Tristan Begg, if he could summarize what the genome shows for the general public.

gave copies to Franz Wegeler and Antonie Brentano. He wrote Antonie:

“many claim to perceive [my] soul clearly in it, I leave that undecided”

(German collected edition letter nr. 897).

Here is what he sent me:

“Genomic analyses of Beethoven’s overall ancestry revealed that he was typical of individuals born in regions bordering Northern, Western, and Central Europe, with the closest affinities to individuals born in and around present-day Germany, France, and the Benelux region. These analyses detected no evidence of recent or substantial non-European admixture, estimating Beethoven’s ancestry to be greater than 99% European. [emphasis mine] A more explicit analysis by FamilyTreeDNA of the most likely locations of Beethoven’s ancestors revealed concentrations of probable ancestor locations around major modern and historical population centers along the Rhine and Moselle Rivers, most notably in regions including Bonn, Cologne, and Trier. While these probable ancestor locations are consistent with Beethoven’s documented ancestry on his mother’s side, an expected concentration of ancestor locations within present-day Belgium, which would have been consistent with the ancestry of Beethoven’s father, was not detected. The researchers could not determine if the absence of Belgian ancestor locations may have arisen from a true lack of Belgian ancestry, or underrepresentation of Belgians within the reference panel used for this ancestry analysis. The majority of Beethoven’s closest living Y-chromosomal, or patrilineal relatives, comprising five living men (as of 2022) who share a common ancestor with Beethoven approximately 1,000 years before present, appeared to have genealogical origins within present-day Germany, while one patrilineal genealogy was traced to Slovakia. Beethoven’s closest living mitochondrial, or matrilineal relatives, had no strong regional affiliation, instead being distributed throughout Europe and among European diasporas.”

The genome thus answers questions that were raised at the beginning of the twentieth century partly based on descriptions of the composer from the composer’s lifetime through the middle of the nineteenth century.

The argument was apparently first made by the African-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor in 1907 based on the composer’s appearance, friendship with the “mulatto” violinist Bridgetower, and character traits. In the 1940s the Jamaican-American Joel A. Rogers addressed the issue in his three-volume Sex and Race, basing his argument especially on Beethoven’s appearance, his life and death masks, and the geographic origins of Beethoven’s family. He suggested that Beethoven had “Negro” ancestors in his Belgian lineage and concluded, “in short, there is no evidence whatever to show that Beethoven was white” (vol. 3, p. 308).

There is an extensive recent literature on the question, including scholarly articles with citations such as Dominique-René de Lerma’s “Beethoven as a Black Composer” in the Black Music Research Journal (spring 1990). An especially useful discussion and analysis of the reasons “Beethoven seems to have been an important symbol to the black community” appears in the chapter “’Beethoven was Black’: Why Does It Matter?” in Michael Broyles’ survey Beethoven in America (Indiana University Press, 2011, pp. 267-91. There he concluded, “Roger’s point that somewhere in Beethoven’s background there may have been Moorish or even, as others have suggested, Sephardic blood can never be fully denied, but barring advances in DNA testing or some as yet unknown scientific methodology, they can never be completely resolved” (p. 272). Exactly those advances have helped us answer these questions, not only in regard to his ancestry but also to the fact that somewhere in the seven generations there was an EPP event (extra-pair paternity) that separated the paternal line from the living Belgian Beethovens.

With the rise of the important United States “Black Lives Matter” movement in 2013 after the murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman (who was acquitted), the question “was Beethoven black?” took on a new significance and new claims were made that this fact had been suppressed. A search of the question on the internet reveals many interesting discussions in the past few years.

Because the issue of how races and identities have been and are represented remains of extraordinary importance today, those questions about Beethoven’s racial identity were reasonable given the absence of the genetic data just recently published. Why consider the question to be reasonable? I do so for three reasons. The first is that far too many writers of music history since the 18th century have frequently either omitted the contributions of women and minorities, misrepresented the contributions of women and minorities, and/or ridiculed theories about how sexual and gender differences affected biography and thus music history. The second reason is simply that almost all repressed and minority groups find both value and validation in celebrating the accomplishments and contributions of famous or celebrated members of their groups, whether they be women, black people, Jewish people, native Americans, and LGBTQIA2S people (a group that often self-identifies now as “queer”), as well as national identity groups, such as Asian-Americans. The third reason is to provide the musicological information given below, which provides some of the original sources used by some proponents of the theory in English and the original German. It’s useful to cite 14 important 19th-century sources that have been referenced as evidence. I give an English translation first and then the original German, both with citations.

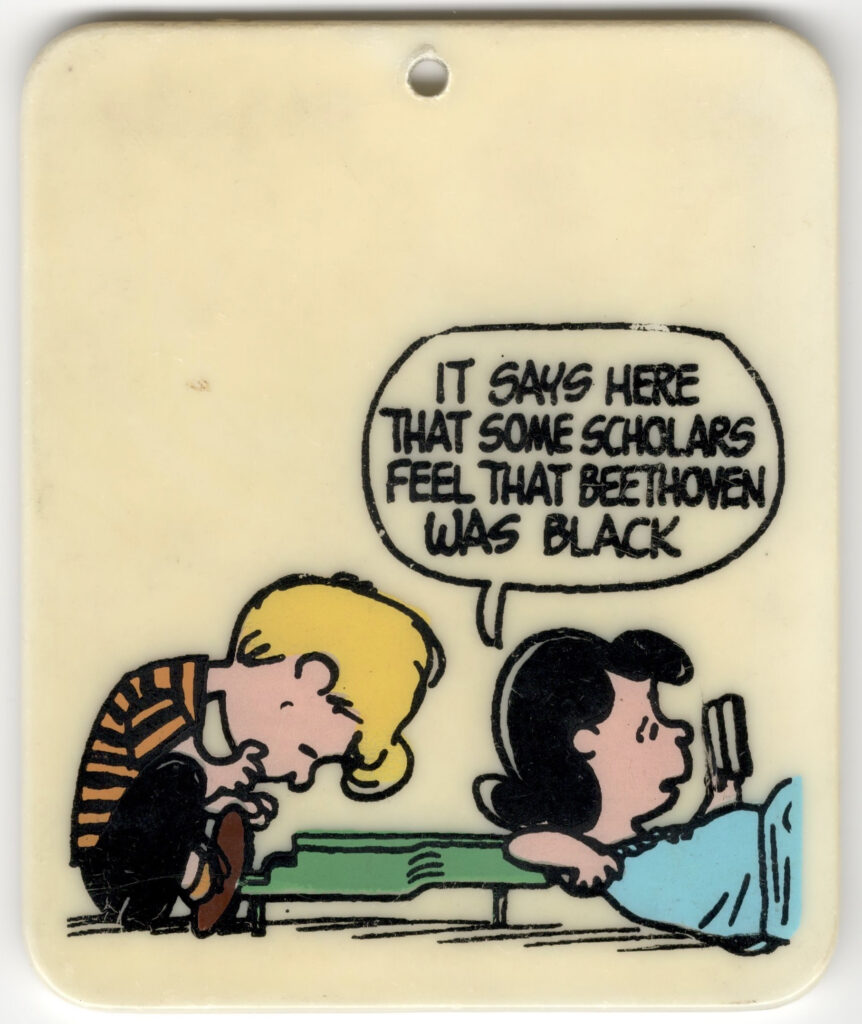

(Peanuts by Charles Schulz for July 07, 1969 | GoComics.com; from the collection of William Meredith)

The most significant descriptions of Beethoven’s dark, swarthy, or red appearance come from the following 14 individuals:

- Cäecilia and Gottfried Fischer about Beethoven’s time in Bonn (1780s)*

- Alexander Wheelock Thayer (around 1792)

- Joseph Gelinek (1793-99)

- Elisabeth von Bernhard née Kissow

- Carl Czerny around 1800*

- Franz Grillparzer around 1805-06*

- Bettina Brentano in 1810*

- Thayer at the time of Charles Neate’s visit in 1815

- August Kloeber in 1818

- Friedrich Rochlitz around 1822

- Carl Maria von Weber in 1823*

- Ludwig Rellstab in 1825

- Anton Schindler in the 1820s*

- Ludwig Nohl (not Fanny Giannastasio del Rio) in 1874, misattributed by Rogers

Authors marked with an * were cited by Joel A. Rogers (Sex and Race, Why White and Black Mix in Spite of Opposition, St. Petersburg, FL.: Helga M. Rogers, 1944, vol. 3, pp. 306-309).

Before looking at the quotes themselves, it is necessary to look at definitions of the German word Mohr to see how the word was understood at the beginning of the 19th century. Although “Moor” is indeed the first translation given, the word was also used to mean black, black-a-moor, negro, and even Ethiopian.

1802: “der Mohr, a Moor, a Black, a Black-a-Moor, a Negro, an Ethiopian.”

(John Ebers {Johannes Ebers], A New Hand-Dictionary of the German Language for Englishmen and of the English Language for the Germans, 2 vols. Halle: Renger Bookseller, 1802, p. 980)

1810: “Mohr, m. moor, negro, black-a-moor”

(Nathan Bailey’s Dictionary English-German and German-English, ed. Johann Anton Fahrenkrüger, 2 vols. Leipzig and Jena: 1810, p. 2:415)

PLEASE NOTE: Finally, the English translations are given as they have appeared in the Beethoven literature rather than being translated anew. These previous translations will allow the readers to follow part of the history of descriptions of his appearance. As can be seen in the example of “Moor” given above, translators have a range of definitions to employ based on their interpretations of the text.

1. 1780s: “dark brown”

Cäecilia Fischer (1762-1845) and Gottfried Fischer (1780-1854), who both knew Beethoven when they were children. Their memoirs were written beginning in 1838. Since Cäecilia was eight years older than Beethoven and Gottfried ten years younger, she is presumed to be the primary source for the information.

“Previous stature of Mr. Lutwig v: Beethoven[.] Short, stocky, broad in the shoulders, short neck, thick head, round nose, dark brown face coloring, he always walked with a stoop. Even as a youngster, he was called the Spaniard in his family.”

(translation based on Wetzstein’s edition cited below)

German original text: “Ehmahliche Stattur, Herr Lutwig v: Beethoven[.] Kurz getrungen, breit in der Schulter, kurz von Halz, dicker Kopf, runde Naß, schwarzbraune Gesichts Farb, er ginng immer was vor übergebükt. Mann nannte ihn im Hauß, ehmal noch alls Junge, der Spagnol.”

(Transcription by Margot Wetzstein in Familie Beethoven im kurfürstlichen Bonn, Bonn: Verlag Beethoven-Haus Bonn, 2006, p. 77)

2. Around 1792: “even more of the Moor in his features” [front teeth, lips, nose, forehead]

Alexander Thayer (1817-1897), the great 19th-century Beethoven biographer

The most recent edition of Thayer’s classic biography, with page citations, is Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, ed. Elliot Forbes, rev. ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967. Thayer himself only finished the first three volumes of the German edition, which appeared in 1866, 1872, and 1879. The fourth volume was prepared by the translator of the first three volumes, Hermann Deiters. Deiters completed the fourth volume but died before it appeared. Hugo Riemann prepared the fourth and fifth editions, which appeared in 1907 and 1908. Riemann revised the first three editions, which appeared in 1917 (vol. 1), 1910 (vol. 2), and 1911 (vol. 3). Thayer never met Beethoven, of course, but because of his authority as a Beethoven biographer, his statement published in 1866 relating Beethoven to Moorish features was influential.

Like the multitude of studious youths and young men who came thither annually to find schools and teachers, this small, thin, dark-complexioned, pockmarked, dark-eyed, bewigged young musician of 22 years [Beethoven] had quietly journeyed to the capital to pursue the study of his art with a small, thin, dark-complexioned, pockmarked, black-eyed, and bewigged veteran composer [Joseph Haydn]. In the well-known anecdote related by Carpani of Haydn’s introduction to him, Anton Esterhazy, the prince, is made to call the composer ‘a Moor.’ Beethoven had even more of the Moor in his features than his master. His front teeth, owing to the singular flatness of the roof of his mouth, protruded, and, of course thrust out his lips; the nose, too, was rather broad and decidedly flattened, while the forehead was remarkably full and round—in the words of Court Secretary Mähler, who twice painted his portrait, ‘a bullet.’” [meaning, musket ball like one used in a pistol; meaning a rough round surface, see, for instance: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/100years/spanish-musket-ball/ ]

(Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, rev. ed. Elliot Forbes, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967, p. 134)

“Gleich der großen Zahl von Studirenden und anderen jungemn Leuten, welche jährlich dorthin kamen, um Unterricht un Lehrer zu finden, war dieser kleine und schmächtige, dunkelfarbige und pockennarbige, schwarzäugige und schwarzhaarige junge Musiker von 22 Jahren in aller Stille zur Hauptstadt gereist, um das Studium seiner Kunst bei dem kleinen und schmächtigem, dunkelfarbigen und pockennarbigen, schwarzäugigen und schwarzgelockten alten Meister weiter zu verfolgen. In der bekannten bei Carpani erzählten Anekdote von Haydn’s Einfuhrung beim Fürsten Anton Esterhazy nennt der Fürst den Componisten einen Mohren. Beethoven hatte noch mehr von einem Mohren in seinem Ausssehen als sein Lehrer. Seine Voderzähne standen in Folge der eigenthümlichen Flachheit seines Gaumens vor und drängten dadurch natürlich die Lippen nach Außen; seiner Nase war breit und platt, die Stirn dagegen merkwürdig voll und rund—nach den Worten des verstorbenen Hofsecretärs Mähler, der zweimal sein Portrait malte, ‘eine Kugel.’”

(Alexander Wheelock Thayer, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Leben, trans. Hermann Deiters, 3 of 5 volumes completed, Berlin: W. Weber, 1866, p. 1:253)

3. 1793 to 1799: “swarthy”

Joseph Gelinek (1758-1825), fortepianist

In his 1842 memoirs Beethoven’s fortepiano student Carl Czerny, who met Beethoven when he was ten, shared two accounts in which Beethoven was described as dark. The first is an anecdote told by the fortepianist Joseph Gelinek (1758-1825), who was apparently trounced by Beethoven in an improvisation contest. Czerny’s father asked Gelinek the name of the man who had trounced him. Gelinek replied,

“He is a short, ugly, swarthy, and obstinate-looking young man, … and his name is Beethoven.”

(This English translation appeared in 1970 as Carl Czerny, On the Proper Performance of All Beethoven’s Works for the Piano, Vienna: Universal Edition, 1970, p. 4).The adjective “schwarz” normally simply means “black,” but in usage the expression “im Geschichte schwarz seyn” means “to look swarthy.” See Nathan Bailey’s Englisch-Deutsches und Deutsch-Englisches Wörterbuch (Leipzig and Jena: Friedrich Frommann, 1810), p. 540. The word “swarthy” was defined as “of dark color, complexion, or cast” as early as 1578. The adjective swarthy does mean “dark skinned,” and was usually used to mean someone whose “skin is weather beaten or darkened by the sun, or has an olive complexion.”)

“Er ist ein kleiner, häßlicher, schwarz und störrisch aussehender junger Mann, … und er heißt Beethoven.”

(For the full German text, see his excerpted “Erinnerungen aus meinem Leben” in Carl Czerny, Über den richtigen Vortrag der sämtlichen Beethoven’schen Klavierwerke, ed. Paul Badura Skoda, Vienna: Universal Edition, 1963, p. 10.)

4. Ca. 1794-99: “red face”

Elisabeth von Bernhard née Kissow (1764-1868), fortepianist who studied with J.A. Streicher

Bernhard was one of the first to describe Beethoven’s complexion as “rote.” The word Roth is defined as “red, rubicund, vermilion” in Ebers 1802 dictionary. However, he added: “eine rothe Gesichtsfarbe, a red or ruddy Complexion. See A New Hand-Dictionary of the German Language for Englishmen and of the English Language for the Germans, ed. John (Johannes) Ebers, 2 vols. Halle: Renger, 1802, 2:1115.

“When he visited us, he generally put his head in at the door before entering to see if there were anyone present he did not like. He was short and insignificant looking, with a red face covered with pock marks.”

(Ludwig Nohl, Beethoven Depicted by His Contemporaries, trans. Emily Hill, 2nd ed. London: William Reeves, 1876, p. 24.)

“Wenn er zu uns kam, steckte er gewöhnlich erst den Kopf durch die Tür und vergewisserte sich, ob nicht Jemand da sei, der ihm mißbehage. Er war klein und unscheinbar, mit einem häßlichen roten Gesicht voll Pockennarben. Sein Haar war ganz dunkel und hing fast zottig ums Gesicht.”

(Die Erinnerungen an Beethoven, ed. Friedrich Kerst, 2 vols., Stuttgart: Julius Hoffmann, 1913, 1: 24. Her memories were first published in Europa, then in the biography by Ludwig Nohl of 1867, 2 vols. 2:18-22.)

5. 1801: “swarthy/brunette face”

Carl Czerny (1791-1857), Beethoven’s student, fortepianist and composer

“Beethoven was dressed in a jacket of shaggy dark grey material and matching trousers, and he reminded me immediately of Campe’s Robinson Crusoe, whose book I was reading just then. His jet-black hair (cut à la Titus) bristled shaggily around his head. His beard, unshaven for several days, made the lower part of his swarthy [sic brunette] face still darker.”

(Carl Czerny, On the Proper Performance of All Beethoven’s Works for the Piano, Vienna: Universal Edition, 1970, pp. 4-5.)

“Beethoven selber war in eine Jacke von langhaarigem dunkelgrauen Zeuge und Gleichen Beinkleidern gekleidet, so daß er mich gleich an die Abbildung des Campe-schen Robinson Crusoe erinnerte, die ich damals eben las. Das pechschwarze Haar sträubte sich zottig /: à la Titus geschnitten : / um seinem Kopf. Der seit einigen Tagen nicht rasierte Bart schwärzte den unteren Theil seines ohnehin brunetten Gesichts noch dunkler.”

(Czerny, Über den richtigen Vortrag der sämtlichen Beethoven’schen Klavierwerke, Vienna: Universal Edition, 1963, p. 10. Importantly, Czerny compared Beethoven’s appearance to that of Robinson Crusoe, marooned on an island and thus with presumably weather-beaten skin. To see the image that Czerny might have had in mind, see the frontispiece in: https://data.onb.ac.at/ABO/+Z35573105 )

(I am indebted to John Wilson for his help locating this image.)

(Campe’s Robinson der Jüngere had been published in 1779/80 and was often reprinted and translated.)

6. 1804-05: “dark”

Franz Grillparzer (1791-1872), poet and librettist

“I first saw Beethoven in my boyhood years—which may have been in 1804 or 1805— … Beethoven in those days was still lean, dark, and contrary to his habit in later years, very elegantly dressed. He wore glasses which I noticed in particular, because at a later period he ceased to avail himself of this aid to his short-sightedness.”

(Beethoven: Impressions by His Contemporaries, ed. O.G. Sonneck (New York: G. Schirmer, 1926, reprint Dover, 1967, p. 154; this book was Rogers’ source)

“Das erstemal sah ich Beethoven in meinen Knabenjahren—es mochte 1804 oder 1805 gewesen sein—, … Er war damals noch mager, schwarz, und zwar, gegen seine spätere Gewohnheit, höchst elegant gekleidet und trug Brillen, was ich mir darum so gut merkte, weil er in späterer Zeit sich diese Hilfsmittels eines kurzen Gesichtes nicht mehre bediente.”

(Die Erinnerungen an Beethoven, ed. Friedrich Kerst, 2 vols., Stuttgart: Julius Hoffmann, 1913, vol. 2, pp. 42-43)

7. 1810: “brown”

Bettina Brentano (1785-1859), composer, political activist, writer

The remarkable Bettina Brentano (later von Arnim) met Beethoven in the summer of 1810 after one of his fantasias (perhaps the first movement of the “Moonlight” Sonata) had made a striking impression on her. Bettina described the composer himself and his apartment in a letter to the Bavarian law student Alois Bihler from July 9, 1810. As I have written (see the publications list), in my estimation Bettina was most likely the famous “Immortal Beloved” of 1812. Her 1810 letter contains this marvelous description of Beethoven’s appearance:

“In person he is small (for all his soul and heart were so big), brown, and full of pockmarks. He is what one terms repulsive, yet has a divine brow, rounded with such noble harmony that one is tempted to look on it as a magnificent work of art. He had black hair, very long, which he tosses back, …”

(Beethoven: Impressions by His Contemporaries, ed. O.G. Sonneck (New York: G. Schirmer, 1926, reprint Dover, 1967, p. 77; this book was Rogers’ source.)

“Endlich kam er. Seine Person ist klein (so groß sein Geist und Herz ist), braun, voll Blatternarben, was man nennt: garstig, hat aber ein herrliches Stirn, die von der Harmonie so edel gewöblt ist, daß man sie wie ein herrliches Kunstwerk anstaunen möchte, schwarze Haare, sehr lang, die er zurückschlägt, …”

(Beethoven aus der Sicht seiner Zeitgenossen in Tagebüchern, Briefen, Gedichten und Erinnerungen, ed. Klaus Martin Kopitz and Rainer Cadenbach, 2 vols. Munich: G. Henle Verlag, 2009, 2:18.)

My friend John Suchet suggested to me that the translation of “garstig” as “repulsive” is inaccurate. Indeed, in one of the quotes included below, it is defined instead as “ugly.” Indeed, this is the definition in Ebers’ 1802 dictionary: “Garstig, adj. häßlich, ungestalt, ugly, disagreeable, deformed, disproportioned, illafavoured. Ein garstiges Gesicht, an ugly Face.” (John Ebers {Johannes Ebers], A New Hand-Dictionary of the German Language for Englishmen and of the English Language for the Germans, 2 vols. Halle: Renger Bookseller, 1802, p. 585).

8. 1815: “dark complexion was very ruddy”

Description by Alexander Thayer at the time that Charles Neate (1784-1877) knew Beethoven.

“At this time, his dark complexion was very ruddy and extremely animated. His abundant hair was in an admirable disorder.”

(Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, rev. ed. Elliot Forbes, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967, p. 620 (A closer translation might be: “His dark complexion was at this time deeply reddened and brightened to a high degree; his abundant hair was in an extraordinary disorder.”))

“Seine dunkle Gesichtsfarbe war in jener Zeit stark geröthet und in hohem Grade belebt; sein üppiges Haar was in wunderlichen Unordnung.”

(Alexander Wheelock Thayer, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Leben, 3 of 5 volumes completed, Berlin: W. Weber, 1879, p. 3:343; p. 506 in the second ed. of 1911 by Riemann)

9. 1818: “healthy and strong complexion”

August Kloeber (1793-1864), painter

“His complexion was healthy and tough [healthy and strong is a better translation], the skin somewhat pock-marked, his hair was of the color of slightly bluish-gray [since it was already changing somewhat from black to gray. His eyes were blue-gray] and highly animated.—when his hair was tossed by the wind there was something Ossianic-demonic about him.”

(Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, rev. ed. Elliot Forbes, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967, p. 703; there are missing descriptions in Thayer-Forbes supplied here in brackets)

(“his hair color was annealed blue steel” is more literal; I would like to thank my friend Dr. Bruce Alan Brown for sharing the meaning of the phrase, though he phrases it in a different way: Under the definition of “anlaufen,” Johann Christoph Adelung [1732-1806] has “Polirten Stahl blau anlaufen lassen, ihm durch das Ausglühen auf der Oberfläche eine blaue Farbe geben,” i.e., what’s called blue annealing in English).

“his hair color was annealed blue steel” is more literal; I would like to thank my friend Dr. Bruce Alan Brown for sharing the meaning of the phrase, though he phrases it in a different way: Under the definition of “anlaufen,” Johann Christoph Adelung [1732-1806] has “Polirten Stahl blau anlaufen lassen, ihm durch das Ausglühen auf der Oberfläche eine blaue Farbe geben,” i.e., what’s called blue annealing in English”

(Ludwig van Beethoven’s Leben von Alexander Wheelock Thayer, ed. Hugo Riemann, 5 vols. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 19, p. 4:105)

10. 1822: “ruddy and healthy color”

Friedrich Rochlitz (1769-1842), music journalist, writer and dramatist

Rochlitz was in Vienna from May 24 to August 2, 1822, where he met Beethoven and described their meetings in letters to his wife Henriette and Gottfried Härtel and also to Anton Schindler.

“Picture to yourself a man of about fifty years, somewhat shorter than the average yet of powerful, stocky build. His bone structure is compact and very strong, something like [the philosopher Johann Gotttlieb] Fichte’s but heavier, especially in the full face. His complexion is ruddy and healthy. His eyes are restless, glowing, and, when his gaze is fixed, almost piercing; if they move at all, the movement is darting, abrupt.”

(as reported in Anton Schindler, Beethoven as I Knew Him, ed. Donald MacArdle, trans. Constance Jolly, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966, p. 454; here the word “rothe” is translated as ruddy, which is in line with early 19th-century dictionaries)

“Denke Dir einem Mann von etwa funfzig Jahren, mehr noch Kleiner, als mittler, aber sehr kräftiger, stämmiger Statur, gedrängt, besonders von starkem Knochenbau—ungefähr, wie Fichte’s, nur fleischiger und besonders von vollerm, runderm Gesicht; rothe, gesunde Farbe; unruhige, leuchtended, ja bei fixirtem Blick fast stechende Augen; keine oder hastige Bewegungen …”

(Beethoven aus der Sicht seiner Zeitgenossen in Tagebüchern, Briefen, Gedichten und Erinnerungen, ed. Klaus Martin Kopitz and Rainer Cadenbach, 2 vols. Munich: G. Henle Verlag, 2009, 2:713-14.)

11. 1823: “dark red face”

Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826), composer, conductor, fortepianist

In 1823 Weber traveled to Vienna for the rehearsals and premiere of his opera Euryanthe on October 23. Beethoven invited Weber to meet him in Baden and the two men with three others had lunch on October 4th. In the biography of his father published in 1864, Weber’s son Max Maria von Weber supplemented the letter his father had written to his wife on October 5th with these additional details, supposedly from “family traditions.”

“His hair was thick, gray, and bristly, here and there altogether white; his forehead and skull had an exceptionally broad curve and were high, like a temple; his nose was four-square, like that of a lion, the mouth nobly shaped and soft, the chin broad, with these wonderful shell-formed grooves in all his portraits, and formed by two jaw-bones which seemed meant to crack the hardest nuts. A dark red overspread his broad, pockmarked face; beneath the bushy, gloomily contracted eyebrows, small radiant eyes beamed mildly upon those entering …”

(Beethoven: Impressions by His Contemporaries, ed. O.G. Sonneck (New York: G. Schirmer, 1926, reprint Dover, 1967, pp. 159-61; this book was Rogers’ source.)

“Das Haar dick, grau, in die Höhe stehend, stellenweise schon weiß, Stirn und Schädel wunderbar breit gewölbt und hich wie ein Tempel, die Nase viereckig wie die einses Löwen, der Munde edel geformt und weich. Über das breite, blatternarbige Gesicht war dunkle Röte verbreitet, unter den finster zusammengezogen buschigen Brauen blickten kleine, leuchtende Augen mild auf die Eintretenden …”

(taken from Julius Kapp, Weber, Stuttgart-Berlin: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1922, p. 190.)

12. 1825: “brownish … transposed into a sickly, yellowish tone”

Ludwig Rellstab (1799-1860), writer, poet, and music journalist

Rellstab met Beethoven during a visit to Vienna from March 30 to May 5, 1825. His reminiscences of Beethoven were first published in 1841 and expanded in a version from 1854. Rellstab’s memories contain many very specific details, such as the fact that Beethoven reportedly told him he could never compose Don Giovanni or Figaro, which he held in “aversion,” because they “are too frivolous for me.” Here is part of his description of Beethoven’s physical appearance from their first visit.

“His hair, almost totally gray, rose bushily and in disorder from his head; not soft, not curly, not stiff, a mixture of all three. … His complexion was brownish, yet not the strong, healthy tan which the huntsman acquires, but rather one transposed into a sickly, yellowish tone. His nose was narrow and sharp, his mouth benevolent, his eye small, light-grey, yet eloquent.”

(Beethoven: Impressions by His Contemporaries, ed. O.G. Sonneck (New York: G. Schirmer, 1926, reprint Dover, 1967, pp. 180; this book was Rogers’ source)

“Das fast durchweg graue Haar erhob sich buschig, ungeordnet auf seinem Scheitel, nicht glatt, nicht Kraus, nicht starr, ein Gemisch aus Allem. … Seine Farbe war bräunlich, doch nicht jenes gesunde kräftige Braun, das sich der Jäger erwirbt, sondern mit einem gelblichkränkelnden Ton versetz. Die Nase schmal, scharf, der Mund wohlwollend, das Auge klein, blasgrau, doch sprechend.”

(Beethoven aus der Sicht seiner Zeitgenossen in Tagebüchern, Briefen, Gedichten und Erinnerungen, ed. Klaus Martin Kopitz and Rainer Cadenbach, 2 vols. Munich: G. Henle Verlag, 2009, 2:682.)

13. 1820s (date not clear): “red and brown”

Anton Schindler, violinist, Beethoven’s volunteer secretary

“His face had a yellowish tinge which, however, disappeared as a result of his continual wandering in the open, especially during the summer, when his full cheeks would be covered with the freshest varnish of red and brown.”

(Beethoven: Impressions by His Contemporaries, ed. O.G. Sonneck (New York: G. Schirmer, 1926, reprint Dover, 1967, p. 166; this book was Rogers’ source. Sonneck compiled a series of paragraphs from, apparently, the 1909 edition of Schindler’s biography edited by Kalischer)

14. 1874 (published 1875/76): “a strong resemblance to a mulatto [Mohrenkopf, the head of a Moor or negro]”

Ludwig Nohl in his edition of diary entries by Fanny Giannatasio del Rio in 1816

J.A. Rogers misatttibuted this quote to Fanny Giannatasio del Rio; it actually came from Ludwig Nohl, the editor. Fanny herself wrote, “He never struck me as an ugly man, but lately his face pleases me, his manners are so original, and all he says has weight.” (See p. 59 of the English translation below.)

“Beethoven could not possibly be called a handsome man. His somewhat broad flat nose and rather wide mouth, his small piercing eyes and swarthy complexion, pock-marked into the bargain, gave him a strong resemblance to a mulatto, and caused many young ladies to pronounce him ‘ugly.’”

(Ludwig Nohl, An Unrequited Love: An Episode in the Life of Beethoven, trans. Annie Wood, London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1876, p. 60.)

“Beethovens Gesicht gehörte allerdings nicht entfernt zu jenen, welche man ‘schön’ nennt. Die etwas platt gedrückte Nase und der ziemlich breite Mund in Verbindung mit kleinen fast stechenden Augen und ein dunkeln und obendrein pockenmarbigen Haut gabe dem Gesicht etwa an einen Mohrenkopf Erinnerndes, das manche junge Dame ‘garstig’ fand.”

(Ludwig Nohl, Ein stille Liebe zu Beethoven, nach dem Tagebuche einer jungen Dame, Leipzig: Ernst Julius Günther, 1985, p. 67)

Postscript on a 2021 request to exhume Beethoven a third time to see if he was black:

In October 2021 the Tunisian-born German actor and singer Roberto Blanco made a request to the Vienna Bürgermeister to dig up Beethoven’s remains in the Central Cemetery in Vienna to see if he was black. The request became international news and was covered in important newspaper and online sources. To the best of my knowledge, nothing has come of this request to date, and now—because of the genome report that covers the composer’s ancestry, among other topics—a third exhumation for this purpose is unnecessary (though it would be useful for medical researchers and scientists for other reasons). On November 1, 2021, Tobias Kemper, a genealogist from Bonn, Germany, published an article in German strongly condemning the request on the basis that it was based on “absurd identity politics” and historical ignorance: https://saecula.de/Beethoven

The title of the article is “Der ‘schwarze’ Beethoven, identitätspolitische Absurditäten, historische Ignoranz” (“’Black’ Beethoven, Identity-Politics Absurdities, Historical Ignorance”). Three German-language sources about Blanco’s request are cited and embedded in the article for those who wish to research the request. Blanco appears in a youtube video speaking about his request: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9jfaw6J9F2s

An English-language article on Blanco’s request by Sophia Alexandra Hall is found on classic fm at: https://www.classicfm.com/composers/beethoven/roberto-blanco-wants-body-exhumed-racial-dna-test/