Alfred Kanwischer’s Egon Petri, Musician to the World, Interviews and Commentary, published by Cuvillier Verlag Göttingen, 2019 (154 pp., can be ordered online for $37.40)

Until performers breath life into them through their imaginations, knowledge, technique, and sensitivities, all the notes on a page of music lie unborn. One of the greatest performers and teachers of the last century who was ever ready to pass on his insights was the German-born Egon Petri.

In 2019 the pianist Alfred Kanwischer—one of the finest professors of piano we ever had at San José State University—published his reminiscences of his teacher Petri (1881-1962) based on weekly interviews made during his teacher’s last year of life. As Alfred, also a Beethoven and Bach scholar, writes in his introduction, “Egon Petri’s story, his performing and teaching art, are as relevant as ever, an invaluable link from the past to the future. His remarks, mottos, and maxims by no means encompass his artistry and instruction, but they do represent his modes of thinking—arresting, penetrating, sensible, time-independent. He was not only a great twentieth-century virtuoso, but also a great teacher” [p. 11].

The book relies on the tapes made in 1961-62 and the almost two hundred pages of exact transcriptions made painstakingly by Alfred’s wife Heidi in 1962-63, as well as Alfred’s recollections of information from personal conversations as well as materials taken from private lessons and masterclasses. Unfortunately, the tapes themselves no longer survive. It would have been wonderful to hear Petri’s voice as he answered Alfred’s questions.

Many of Petri’s performances are accessible on YouTube. Even better, numerous original copies of his sound recordings are for sale on eBay for reasonable prices. The sound quality on those records is much superior to any CD, and I recommend them as first access, in part because Petri, as you can read below, was famous for his sense of color at the piano.

As I read through Alfred’s study, I marked all of the pages that contain significant Beethoven content, and I realized it would be useful to gather a number of them together here. (Unfortunately, the book does not contain a name index, but Alfred and I have added five indexes below.) Because Alfred intermixes Petri’s quotes with his own words and to make the sections easier to understand, everything is directly from the book except for those occasions when I added introductions to material. My introductions are in italics and marked by “WM.”

***

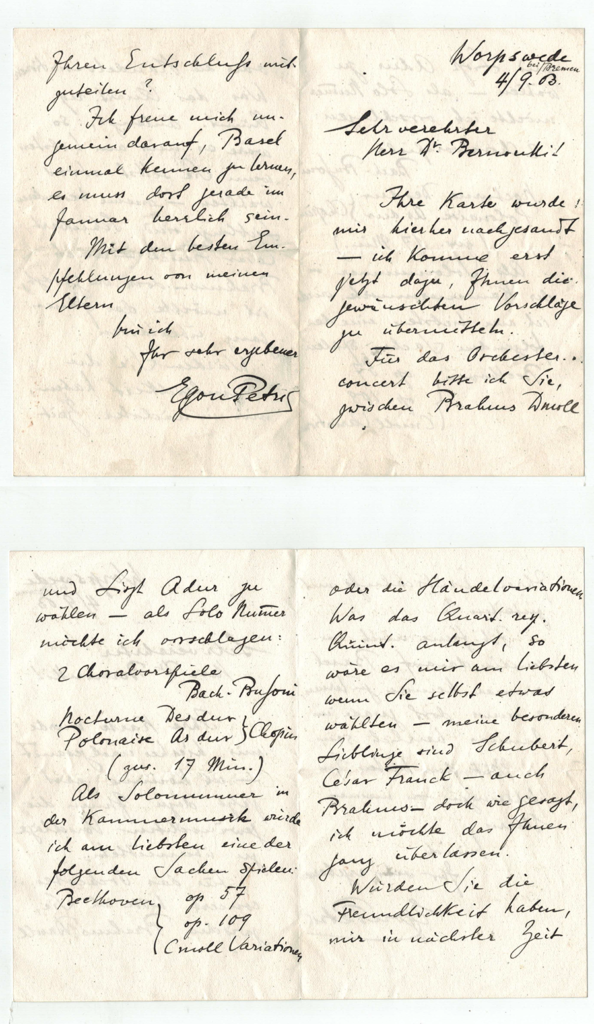

Letter from the twenty-two-year old Egon Petri to a member of the distinguished Bernoulli family of Basel from September 4, 1903 detailing his suggestions for the repertory for a forthcoming orchestral concert (the Brahms Concerto in D Minor or the Liszt Concerto in A Major). As solo numbers he would like to play 2 Choralvorspiele in the Bach-Busoni arrangements and a nocturne and polonaise by Chopin). As solo numbers in the chamber music set, he would most like to play Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata, Opus 57; the Sonata in E Major, Opus 109; and the Variations in C Minor, WoO 63 or 80 (or the Handel Variations, ?WoO 45). (From the collection of William Meredith)

Petri’s Beethoven Reminiscences Through his home years … Egon also played the piano for his father’s chamber music sessions, on the Blüthner grand piano at home, or sometimes elsewhere. “I once played the Kreutzer Sonata [Opus 47] with my father in a private home in Weisenberg in Bremen,” he recalled. “I was very young and enthusiastic and we came down to the theme in the middle, and I just went to town, and I played it and enjoyed it very much. Suddenly, my father put down his violin and said, ‘Please give me a trombone!’ I was playing so loud I was just killing him, So, one learns.” [p. 29; Kanwischer wrote me that he had “always assumed it was the first movt., already possibly from bar 61+. If not there, by bars 122+. Or, possibly all the octave stuff in the development, bars 210+.” (Letter of November 1, 2023)]

For a performance not by Petri but with a score, see:

I took the marks [from a recording contract] and visited [the famous violinist Adolph] Brodsky in Marienbad [Austria]. … Now Brodsky said, “Petri, do you know the Kreutzer Sonata?” “Of course, I’ve played it with my father.” Brodsky said, “I have no music here,” and I said, “I have no music,” and he said, “Well, just let’s play it together.” I said, “fine.” … I knew it from memory. So, we played it together and he was convinced that I could do something. And he made me play other things and was very, very satisfied. He went back to [the Royal College of Music in] Manchester [England] … and proposed my name for the teaching position. On the first of October [1905], I got a telegram, “You are appointed.” [pp. 42-43]

While conversing on the subject of Beethoven, Egon once told us: “My father had a friend called Dr. Seymond, who lived in Bonn, where Beethoven was born. He lived in a three-story house. One day, Seymond went up to the attic, probably not alone, with his servants, and told them to wrap up all these old papers with string, and sell them to the grocery store down the block, where they were used to wrap the herring and the cheese. As he was supervising the packing, his eyes fell on some notes, and he pulled this paper out, and it was the original manuscript of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 26.” [pp. 60-61]

WM: When Petri’s father was considering whether or not Egon should become a professional pianist, he turned to Ignace Jan Paderewski (1860-1941).

After hearing Egon play the piano, Paderewski advised a career as a pianist. As Egon said, “Paderewski’s advice was really a turning point for me. I had great admiration for him.” However, of Paderewski’s playing, Ego said, “Paderewski was very, very free … too free sometimes.” For example, he suggested Egon take many more freedoms of tempo in his performance of the opening movement of Beethoven’s Op. 109 [the late sonata in E Major] (as did Busoni). Petri’s conservative ideals at that moment may have come partially from his father’s more fastidious approach. … As Petri recalled, “I learned very much … that there is a fine balance between playing too much in time and too much rubato.” (Paderewski’s rubato was both famous, and infamous.) “You can go too far. You mustn’t obscure the meter by freedom of playing. It’s not a question of this or that—but how much.” [pp. 65-66]

WM: A live performance of the sonata by Petri is available on YouTube, see below for link. I have also included two Paderewski performances of the “Moonlight” Sonata, one a video.

Another critical influence on young Petri was Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924):

Petri was drawn to his charisma, riveting pianism, wide education, analytical powers, fierce intellect, and visionary ideals. “I owe most of my introduction to literature to Busoni … He gave me [Hans Christian] Anderson stories when I was a boy. He introduced me to George Bernard Shaw, to [Edgar Allen] Poe, to E.T.A. Hoffmann, and all the German romantics.” … being original in a different way, Busoni once collaborated with Mahler to remove all “traditonal” performance conventions from the Emperor Concerto of Beethoven, to develop a new fresh interpretation derived only from the score alone. Thus Busoni went beyond Mahler’s potent dictum, “Tradition is tending the flame, not worshipping the ashes.” [pp. 68-69, 71]

Busoni could be playful, as Egon recounted, unusual for that time. Busoni had performed the Beethoven piano concertos using Beethoven’s own cadenzas. A critic wrote, “The concerto was played very beautifully, but the cadenzas of Busoni were absolutely out of style.” Busoni rang the critic up at 7 o’clock in the morning at his home —the critic was just getting out of bed—and Busoni spoke very deeply over the phone, “Hier Beethoven, did Cadenzen von mir!” (“This is Beethoven. The cadenzas are mine!” [p. 72]

When Busoni was only 21 in 1902, he heard the great Belgian violinist Eugene Ysaye (1858-1931) play Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Petri commented, “Ysaye had a wonderful freedom in his playing … It wasn’t so set and regular as I was used to hearing it. So I admired it very much.” Egon was introduced to Ysaye by Busoni after the concert. He stared at Egon, then intoned “Du muss arbeit!” (You must work!). “Busoni played with Ysaye quite a bit,” Egon recalled later. “I heard Ysaye play the Beethoven Concerto and I said to my friends, ‘It was like a meadow of flowers—so beautiful in colors.'” [p. 79]

As Petri said, Busoni “insisted that without knowing all of Beethoven, you could not sit down at the piano and profess to really understand the ‘Appassionata’ Sonata.” Petri declared, over all, “Busoni succeeded in equipping his students with that most valuable possession—independence of thought and spirit.” [p. 91]

WM: Another Petri quote about the sonata concerned the necessity for performers to read great literature and try to understand the literature and spirit of an age:

“Of course, if you are not a musician, then this information doesn’t help you at all. You can’t play the ‘Appassionata’ Sonata by reading biographic materials about Beethoven and his times. … But, (if you are a musician), it most certainly helps to know something about the times of the composer.” [p. 109]

About Petri’s great affinity for Beethoven, in 1959, at the San Francisco Museum of Art, he performed all thrity-two sonatas in a series of six concerts. When he played the opening movement of the “Moonlight” Sonata, veiled, ghostly, harp=like sonorities emerged, seemingly from another world, whereby it seemed as if he kept the damper pedal depressed for the whole movement (as Beethoven notates in his scroe). It was uncanny, the audience transfixed—and this on a newer American Steinway. Years later, in 1968 Mrs. Kanwischer and I were powerfully reminded of this during our visit to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, where we played on Beethoven’s own original pianos, the Erard grand of 1803 and the Broadwood of 1807. When Mrs. Kanwischer played the opening movement of the “Moonlight” on those pianos, we realized with a start that Egon, back in 1959, had so closely approximated thsoe ethereal, ghostly harp-like sonorities. [pp. 115-16]

WM: One of my favorite anecdotes in the book concerns Brahms, not Beethoven, and it is a favorite because I first heard it as a first-year masters student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in a course on Brahms taught by the famous William S. Newman in the fall of 1976 or spring of 1977. Here is Petri’s telling of the story:

There was the American Quartet at the time that Brahms was still alive. I don’t know whether it is true or not, but still, the story has a germ of truth. They had played the Brahms quartets and loved them very much, and they toured in America. They played them at a certain tempo, and Brahms was still alive. The first violinist said, “You know, we have an engagement in Germany, in Austria, and I will write Brahms and ask him if he would be gracious enough to listen to our playing and tell us his opinion of the quartets. Brahms wrote a very nice letter back, “I will be pleased to listen to you at such and such a time, in my rooms.” Then the first violinist said, “I know Brahms, and I know he likes very slow tempos, so let’s slow our tempos to about half of what we have been playing in America!” They had quite a bit of trouble holding back, but they got used to it, and were able to do it at reduced speed. And then they came to Brahms. After they had finished playing, Brahms said, “Bravissimo, bravissimo, Gentlemen … but please, why so quick?” [pp. 105-06]

WM: There is some problem with the details here as Brahms died in 1897

Several recommended YouTube recordings:

J.S. Bach, “Sheep May Safely Graze,” his arrangement, recording from 1958 (at a beautiful moving tempo and beautifully phrased):

A much slower and gentler performance (with incredible voicing of the melody) and with the score:

J.S. Bach Chaconne, in the arrangement by Busoni:

Beethoven, Sonata, Opus 109, in a live recording from 1954:

PADEREWSKI

Beethoven, “Moonlight” Sonata, complete, sound recording:

1. Paderewski plays Beethoven “Moonlight” Sonata (at 18:50), Chopin, Schubert, Mendelssohn (piano rolls, vinyl)

Made from a Duo-Art piano roll, really worth paying attention to for many performance practice reasons (especially the quick tempo in which one hears the cut-time time signature; the performance of the dotted notes against the triplets; the development section at 20:46 with the change of tempo and the left hand; and the beauty of the descending notes in the right hand at 22:13).

2. Video performance of the first movement from 1937 at a slower tempo (not as interesting as the Duo-Art piano roll, and you have to watch a silly video that should be called “The Kiss”:

Schubert, Impromptu, Opus 142/2, at 37:31

Five Indexes to Alfred Kanwischer’s

Egon Petri, Musician to the World: Interviews and Commentary

(Göttingen, Germany: Cuvillier Verlag, 2019)

Because Dr. Kanwischer’s book was published without any indexes, I compiled the first four indexes to make its information more readily accessible. The amount of information on Ferrucio Busoni (1866-1924), for example, is impressive but spread throughout the book. See his entries below both as a teacher and composer. My four indexes are found below: (1) Performers and Ensembles, (2) Teachers and Editors that Petri Studied, (3) Composers, and (4) Famous Non-Musicians. I asked Dr. Kanwischer to add an index on piano techniques and approaches (5).

I have not included the names of secondary authors included. Except for the section listed in Teachers, Petri’s parents, Kathi and Henri, are omitted here as they are mentioned throughout the book. The section of composer’s names does not include the names in the Appendix, which is an alphabetical index by genre of composer’s works that Petri performed.

An * is used to indicate a page with a fascinating or important anecdote.

(1) Performer and Piano Builders’ Index

American Quartet [probably=Kneisel Quartet]: 105-106*

Argerich, Martha: 50

Bachhaus, Wilhelm: 31, 33-34

Barber, Samuel: 101

Barbirolli, John: 51

Barenboim, Daniel: 50

Bechstein, Carl Wilhelm Friedrich (1826-1900): 45-47, 50-51

Bechstein, Carl and Helene (Hitler financier): 45

Berlin Philharmonic: 75

Berlin State Opera Orchestra: 20, 76

Bernbaum, Zdislaw: 58

Bernstein, Leonard: 58, 101

Blüthner, Julius: 23, 29, 44, 46

Bolt, Adrian: 51

Borge, Victor: 101

Bösendorfer (pianos): 46, 50

Boston Symphony: 53

Brahms, Johannes: 40

Breithaupt, Rudolph: 26

Blinder, Naoum: 43

Broadwood (fortepianos): 115-16

Brodsky, Adolph: 42, 43*, 44

Budapest Quartet: 41*

Busotti, Carlo: 115

Capet, Lucien: 101

Casadesus, Gaby: 101

Casadesus, Jean: 101

Casadesus, Robert: 99, 101

Chicago Symphony Orchestra: 28

Cliburn, Van: 49

Concertgebouw, Amerstdam: 47, 52-53

Damrosch, Walter: 33

Diémer, Louis: 101

Dresden State Opera Orchestra: 22, 24, 57

Ehrbar (pianos): 46*

Elgar, Edward: 55

Erard (fortepianos and pianos): 46, 115-16

Essipoff, Anna: 101

Fay, Amy: 85

Fazioli (pianos): 50

Foss, Lukas: 101

Gieseking, Walter: 50-51

Gewandhaus Orchestra, Leipzig: 22, 36, 75

Gibson, Henry: 101

Goer, Walter: 93

Gottschalk, Louis: 25

Gould, Glenn: 50, 57, 118

Graffman, Gary: 101

Halle orchestra: 43, 55

Hanover Royal Opera Orchestra: 22

Hellmesberger, Joseph: 42

Hewitt, Angela: 50

Horowitz, Vladimir: 50, 67

Ibach (piano): 46

Istomen, Eugene: 100

Janis, Byron: 49

Joachim, Joseph: 21, 31, 33, 39-40, 75, 77, 80

Joachim String Quartet: 75

Joachim, Kathi: 76

Johannesen, Grant: 99-100, 115*

Johansen, Gunner: 100

Kärthnerthor Theater: 54

Kleiber, Eric: 51

Klemperer, Otto: 45, 51, 104

Kneissel Quartet [probably; Petri called them the American Quartet]: 106-106*

Koussevitsky, Serge: 51

Kullak, Theodor: 85

Leinsdorf, Erich: 49

Leipzig Theater: 22

Levy, Ernst: 100

Lipati, Dinu: 46

Liszt, Franz: 23, 28, 35, 53, 63-64, 67-68, 85

London Philharmonic: 54

London Symphony: 93

Mahler, Gustav: 44

Marsch, Ozan: 100

Mengelberg, Willem: 20, 47, 51-52

Michelangeli, Arturo: 50

Mitropoulos, Dimitri: 51, 58

Molinari, Bernardino: 51

Morales, Erica: 101

New York Philharmonic: 43

New York Symphony Orchestra: 33

Nikisch, Arthur: 22

Nottingham Orchestra: 53

Ogden, John: 100

Ohlsson, Garrick: 50

Paderewski, Ignace: 34, 39, 68

Henri Petri Strinq Quartet: 24, 29, 57, 78

Petri, Martinus (oboist and organist); 20

Petri, Willem (cellist, violinist, pianist): 20

Ponti, Michael: 36

Pro Arte Quartet: 115

Rachmaninoff, Sergei: 35, 44, 66*

Reckendorf, Alois: 33

Reinecke, Carl: 35-36

Richter, Hans: 51, 54-56*, 57, 64, 118

Richter, Sviatoslav: 48-49

Rodzinski, Artur: 51

Rubenstein, Anton: 25, 31, 35, 49-50, 66-68, 80, 101

Safonoff, Wassily: 67

San Francisco Symphony: 12, 43

Savoy Theater: 53

Schiff, Andras: 50

Schnabel, Artur: 12, 46, 49-50, 67

Schumann, Clara: 31-32, 40, 85, 106-107, 109, 117

Seifert, Uso: 30

Serkin, Rudolph: 70

Siloti, Alexander: 35

Slenzynska, Ruth: 100

Slonimsky, Nikolas: 101

Steuermann, Edward: 74

Steinway (pianos): 46-51

Stern, Isaac: 43, 79, 100, 120

Stock, Frederick: 28, 51

Strauss, Richard: 31, 33

Szigeti, Joseph: 29-30, 45, 104

Tausig, Carl: 63, 85

Tchaikovsky, Peter: 31*, 35

Toscanini, Arturo: 45, 120

Tovey, Donald: 12

Vengerova, Isabella: 26

Vienna Philharmonic: 54

Vronsky, Vita: 100

Walter, Bruno: 45, 51, 58

Watson, Gordon: 58

Weber, Carl (conductor): 106

Weigert, Marta: 70, 90-93

Weimar Orchestra: 75

Weiss, Edward: 66, 71-72

Wilde, Earl: 100

Wood, Henry: 51, 53-54, 114

Yamaha (pianos): 50

Ysaye, Eugene: 78-80

Zakin, Alexander: 100

(2) Petri’s Teachers and Teachers and Editors He Studied Index

Badura-Skoda, Paul and Eva: 98

Böhm (piano): 25, 84

Breithaupt, Rudolf: 83-85

Buchmayer, Richard (piano): 38

Busoni, Ferrucio (piano): 24-25, 27-28, 40, 42-43, 62, 67, 68-69, 70*, 71*, 72-73, 74*, 76-80, 87-94, 98, 101, 107, 115, 119

Carreño, Teresa (piano): 25-26, 63, 84

Czerny, Carl: 84

d’Albert, Eugene: 25-27, 33, 63-65, 72, 80, 92, 102

Deppe, Ludwig: 83, 85

Draeseke, Felix (theory): 38

Kirkpatrick, Ralph: 98

Kretzschmar, Herman (composition): 38

Leschetizky, Theodor: 83-84, 101

Matthay, Tobias: 83-84, 86

Ortmann, Otto: 83-84, 95*

Paderewski, Ignacy: 62, 65-66

Petri, Henri Wilhelm: 75-76

Rubenstein, Anton: 63

Schnabel, Artur: 98

Schultz, Arnold: 83-84

Schweitzer, Albert: 98

Tovey, Donald: 94-95

von Bülow, Hans: 98

Walter, Bruno: 104

Wieck, Frederick: 85

Whiteside, Abby: 83-84, 86

(3) Composer Index

Alkan, Charles-Valentin: 111

Bach, J.S.: 15, 24-25, 30-31, 36, 38, 49, 59, 62, 66, 91, 94, 96-99, 106, 111-13, 121

Barber, Samuel: 49

Bartok, Bela: 45

Beethoven, Ludwig: 12-13, 21-23, 29, 33-34, 38-44, 46-48, 50, 52, 58-61, 63*, 64-66, 67*, 68, 71*, 72-73, 78-79, 85, 90-92, 94, 96-100, 103, 107, 111-13, 115-16, 118-121

Brahms, Johannes: 12, 21, 29-30, 31*, 32*, 34-35, 40*, 43-44, 49, 55, 64, 75-78, 80, 85, 96, 105-106*, 111-13, 117

Busoni, Feruccio: 13, 23-24, 31, 40, 46, 49, 65, 111-12, 114*, 121

Casella, Alfredo: 111

Chopin, Frederic: 13, 41, 49, 62, 66, 70-71, 93, 96-97, 111, 113, 120*, 121

Czerny, Carl: 25

Debussy, Claude: 46*, 50, 52, 72

Fauré, Gabriel: 115

Franck, César: 13, 30, 57, 60-61, 79, 112

Glazunov, Alexander: 111

Gounod, Charles: 13

Grieg, Edvard: 31

Griffes, Charles: 111

Handel, Frederic: 112

Hasse, Johann: 38

Haydn, Joseph: 16, 38, 72, 96, 18

Liszt, Franz: 13, 21, 30, 34, 35*, 54*, 60, 66, 69-70, 74, 91, 93, 98*, 103, 107, 111-14, 117, 121-22

MacDowell, Edward: 26

Mahler, Gustav: 31*, 52, 71*, 117

Medtner, Nikolai: 13, 111

Mendelssohn, Felix: 13, 22, 36, 64, 75, 106, 108, 111

Milhaud, Darius: 115

Mozart, Wolfgang: 13, 16, 24, 34, 38-39, 64, 68-69, 71-72, 96*, 97, 101, 105, 111-12, 118

Paderewski, Ignacy: 66

Paganini, Nicolo: 79, 112

Prokofieff, Sergei: 111

Rachmaninoff, Sergei: 111

Ravel, Maurice: 46, 50

Reger, Max: 30

Reinecke, Carl: 36

Rubenstein, Anton: 35

Saint-Saëns, Camille: 52

Scarlatti, Domenico: 94

Schoenberg, Arnold: 71, 74*, 111

Scriabin, Alexander: 49, 111

Stravinsky, Igor: 111

Schubert, Franz: 21, 34, 44, 58*, 62, 111-12, 122

Schumann, Robert: 29, 35-36, 66, 68, 99, 106-107, 109, 111, 119

Spohr, Louis: 44

Strauss, Richard: 33*, 52

Tchaikovsky, Peter: 43, 93, 112, 117

Wagner, Richard: 39, 46, 54-58, 106, 117

(4) Famous Non-Musicians

Anderson, Hans-Christian: 69

Brown, Jerry: 100

da Vinci, Leonardo: 87

Dickens, Charles: 16

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang: 38, 70

Grey’s Anatomy: 95

Heraclitus: 94

Hitler, Adolf: 45, 53*, 103-104

Hoffmann, E.T.A.: 69, 106

James, William: 80

Nabokov, Vladimir: 99

Novalis: 106

Richter, Jean Paul: 106

Rilke, Rainer Maria: 36-37

Rodin, Auguste: 37

Schlegel, Friedrich: 106-107

Schiller, Friedrich: 38

Seymond, Dr. (from Bonn): 60

Shakespeare: 38

Shaw, George Bernard: 69

Trotsky, Leon: 49

Vogler, Heinrich (illustrator): 36-37

Westhoff, Clara (sculptor, Rilke’s wife): 36-37

Wilhelm III, King of Holland: 75, 77

(5) Piano Techniques and Approaches

(compiled by Dr. Kanwischer)

Barenboim: 50

Böhm: 25

Breithaupt: 26, 85

Busoni: 27-28, 46, 68-74, 87-94, 119

Carreno: 25-26, 84

Casadesus, Robert: 99, 101

Czerny: 25, 84

Debussy: 46, 50

Deppe: 85

Erard: 115-16

Fay: 85

Gieseking: 50-51

Gould: 50

Henle: 50

Hewitt: 50

Horowitz: 67

Kirkpatrick: 98

Kullak: 85

Leschetizky: 84

Lipatti: 46

Liszt: 23, 63-64, 67, 85

Matthay: 86

Ohlsson: 50

Ortman: 84, 95

Paderewski: 65-66

Petri, Egon: esp. 25, 51, 83-90, 91-92, 95-98, 115-16

Petri, Henri: 77-78, 79

Ravel: 46

Rubenstein, Anton: 66-67, 68

Schiff: 50

Schnabel: 46, 67

Schultz: 84

Schumann, Clara: 85

Schweitzer: 98

Serkin: 70-71

Tovey: 94-95

Vengerova: 101

von Bülow: 98

Wagner: 46

Weigert: 90-92

Weise, Edward: 71

Whiteside: 86

Wieck: 85