Question: Did Anton Schindler—Beethoven’s volunter assistant from roughly January 1823 through May 1824 and from December 8, 1826, till the composer’s death in March 1827—have a visitor’s card in Paris that identified himself as a “Friend of Beethoven” (“l’Ami de Beethoven”)?

Short answer: False. There is no evidence for this assertion, which has as its sole source unreliable gossip from a famously sarcastic German poet (and occasional blackmailer) named Heinrich (“Harry”) Heine (1797-1856) in April 1841. Heine himself mockingly corrected his mistake in March 1843 in an apology that has too often escaped attention. (A canard is “a false or unfounded report or story, especially a fabricated report”; Merriam-Webster Dictionary.)

The history: In the April 29, 1841, issue no. 119 of the Beilage zur Allgemeine Zeitung—the Allgemine Zeitung was the most important daily newspaper in Germany until 1866—Heinrich Heine included the following paragraph on Schindler in his April 20, 1841, unsigned report on the “Musikalische Saison in Paris” (p. 945):

“Less ghastly than Beethoven’s music did I find Beethoven’s friend, l’Ami de Beethoven, as he everywhere produced himself here, I believe even on his visiting-cards. A black hop-pole with a terrible white cravat and a funereal countenance. Was this friend of Beethoven’s really his Pylades? Or was he one of those indifferent acquaintances whose company a man of genius enjoy all the more, perhaps, at times, the more insignifcant they are, and the more prosaic is their chatter, which refreshes him about exhausting poetic flights on the wings of the spirit. At any rate, we have [sic, saw] here a new manner of exploiting genius, and the little papers make not a little fun of l’Ami de Beethoven. ‘How could the great artist find such an unedifying, mentally impoverished friend supportable?” cried the French, who lost all patience at the monotonous chatter of their tiresome guest. They did not remember that Beethoven was deaf?”

(Translation from Heinrich Heine, “Heinrich Heine’s Musical Feuilletons [Concluded],” ed. O.G. Sonneck, trans. Frederick Martens, Musical Quarterly 8, no. 3 (July 1922): 437. www.jstor.org/stable/738167)

Notes:

1. A hop-pole is a tall pole stuck in the ground to hold the wires that hop vines grow up.

2. Pylades was Orestes’s closest friend who convinced Orestes, according to mythology, to go through with his plan to murder his mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus in revenge for her killing Orestes’s father Agamemnon. Beethoven scholar John Wilson writes me that in “Anton Reicha’s autobiography, sections of which made it into the various obituaries published by his students in the late 1830s, he famously says he and Beethoven were ‘like a second Orestes and Pylades in our youth.’” Thus, Heine’s question may have been related to the publication of sections of Reicha’s autobiography in the 1830s. Reicha (1770-1836) moved to Bonn with his uncle in 1785. Reicha wrote, “Like Orestes and Pylades, we were constant companions during fourteen years of our youth.” Reicha was including the seven years in Vienna till 1792 and seven more years in Vienna. For more information, see the entry on Reicha in Peter Clive’s valuable Beethoven and His World: A Biographical Dictionary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 279-80. (Clive carefully wrote that “Heine even suggested, maliciously, that Schindler had the words L’ami de Beethoven engraved on his calling card” [p. 314].)

Heine’s original German is:

“Minder schauerlich als die Beethoven’sche Musik war für mich der Freund Beethovens, l’Ami de Beethoven, wie er sich hier überall producirte, ich glaube sogar auf Visitenkarten: eine schwarze Hopfenstange mit eine entsetzlich weißen Cravatte und einer Leichenbittermiene. War dieser Freund Beethovens wirklich dessen Pylades? Oder gehörte er zu jenen gleichgültigen Bekannten, mit denen ein genialer Mensch zuweilen um so lieber Umgang pflegt, je unbedeutender sie sind und je prosaischer ihr Geplapper ist, das ihm eine Erholung gewährt nach ermüdend poetischen Geistesflügen? Jedenfalls sahen wir hier eine neue Art der Ausbeutung des Genius, und die kleinen Blätter spöttelten nicht wenig über den Ami de Beethoven. ‘Wie konnte der große Künstler einen so unerquicklichen, geistesarmen Freund ertragen!’ riefen die Franzosen, die über das monotone Geschwätz jenes langweiligen Gastes alle Geduld verloren. Sie dachten nicht daran, daß Beethoven taub war.”

See https://digipress.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb10504344_00451_u001/1

The preceding paragraph in Heine’s report should have been plenty to throw suspicion on his judgments, as there he confessed that Beethoven’ music makes him “shudder with a dread I cannot conceal” and that “his last works bear a gruesome death-mark on their foreheads.” Indeed, Heine’s music reports are not infrequently catty and sharply vicious (he wrote, for example, that when he saw Meyerbeer, “I thought of the diarrheal god of Tartarian folk-legend,” p. 440).

Heine himself explicitly refuted his assertion about the “l’Ami de Beethoven” card in a later issue of his reports (Second Report, March 26, 1843), even if he did so with arch self-satisfaction and additional snideness:

“I will conclude this article with a kind deed. As I am informed, M. Schindler in Cologne, where he is a musical conductor, is greatly grieved because I spoke slightingly of his white cravat, and as regards himself, have declared that on his visiting-card, beneath his name, one might read the addition, L’Ami de Beethoven. The latter fact he denies. With respect to the cravat, what was said was entirely correct; and I have never seen a monster more horribly white and stiff; yet as regards the card, I am constrained by my love for humankind to admit I myself doubt whether these words were really engraved upon it. I did not invent the tale, but, perhaps, gave it too ready a credence, as is the case with all things in this world, where we pay more attention to plausibility than to the actual truth. [boldface my addition] The story shows that the man was held capable of such a piece of foolishness, and gives us the real measure of his personality, whereas an actual fact in itself alone could be no more than a chance, without any characteristic meaning. I have not seen the card in question; [boldface mine] on the other hand I did see, lately, with my own eyes, the visiting-card ofa poor Italian inger, who had had the words ‘M. Rubini’s nephew,’ printed beneath his name.”

(p. 454)

The original German is:

“Ich will diesen Artikel mit einer guten Handlung beschließen. Wie ich höre, soll sich Herr Schindler in Köln, wo er Musikdirektor ist, sehr darüber grämen, daß ich in einem meiner Saisonberichte sehr wegwerfend von seiner weißen Kravatte gesprochen und von ihm selbst behauptet habe, auf seiner Visitenkarte seiunter seinen Namen der Zusatz ‘Ami de Beethoven’ zu lesen gewesen. Letzteres stellt er in Abrede; was die Kravatte betrifft, so hat es damit ganz seine Richtigkeit, und ich habe nie ein fürchterlich weißeres und steiferes Ungeheuer gesehen; doch in betreff der Karte muß ich aus Menschenliebe gestehen, daß ich selber daran zweifle, ob jene Worte wirklich darauf gestanden. Ich habe die Geschichte nicht erfunden, aber vielleicht mit zu großer Zuvorkommenheit geglaubt, wie es denn bei allem in der Welt mehr auf die Wahrscheinlichkeit als auf die Wahrheit selbst ankommt. [boldface mine] Erstere beweist, daß man den Mann einer sochen Narrheit fähig hielt, und bietet uns das Maß seines wirklichen Wesens, während ein wahres Faktum an und für sich nur eine Zufälligkeit ohne charakteristische Bedeutung sein kann. Ich habe die erwähnte Karte nicht gesehen; [boldface mine] dagegen sah ich dieser Tage mit leiblich eigenen Augen die Visitenkarte eines schlechten italienischen Sängers [A. Gallinari], der unter seinem Namen die Worte: Neveu de Mr. Rubini hatte drucken lassen.”

Note: The German text is taken from a report dated March 26, 1843, in the “Musikalische Berichte” section titled Lutetia II, in Heinrich Heine’s Gesammelte Werke, ed. Gustav Karpeles, vol. 7, 2nd ed. (Berlin: G. Grote’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1893), pp. 214-15 (Lutetia, letter LVI). Martens’ 1922 translation in Musical Quarterly was not based on the report “Musikalische Saison in Paris. Paris, 20 März” in the Außerordentliche Beilage zu Nr. 35 der Allg.[emeine] Zeitung, March 26, 1843, pp. 10-12 (which has a different date, is quite shorter, and does not contain this visiting card paragraph). There are also significant variants in the French version of Lutetia, though not apparently regarding this paragraph. Only portions of the text of the “Second Report, Paris, March 26, 1843” on pp. 449-454 in Martens’s translation are in the Allgemeine Zeitung Beilage of March 26.

Even though Heine retracted his assertion about the calling-card, the false story made itself into the world of Beethoven reception, included in both biographies and the public imagination. It has been refuted, including by none other than the great American Beethoven scholar Alexander Wheelock Thayer. In Sir George Grove’s entry on Schindler in the first edition of his dictionary, he wrote that Thayer had told him that the claim about the card was not authentic and was merely a joke. (It was not actually a joke but a nasty piece of fake gossip.)

The anecdote continued to circulate to such a degree that, in 1927 on the occasion of lightly editing a fifth edition of Schindler’s biography of Beethoven, the scholar Fritz Volbach also explicitly refuted it in his preface, which is a short biography of Schindler:

“[In Paris] he also met the poet Heinrich Heine. Heine, however, attacked Schindler in a hateful manner in the newspaper and tried to make him laughable. From Heine came the false assertion that Schindler called himself ‘friend of Beethoven’ on his visiting card. Schindler characteristically and in brief called Heine ‘an excellent poet, but bad man.’”

(Fritz Volbach, “Anton Felix Schindler,” introduction to Anton Schindler, Ludwig van Beethoven, ed. Fritz Volbach, 5th ed. (Münster: Aschendorf Verlagbuchhandlung, 1927), XVIII.

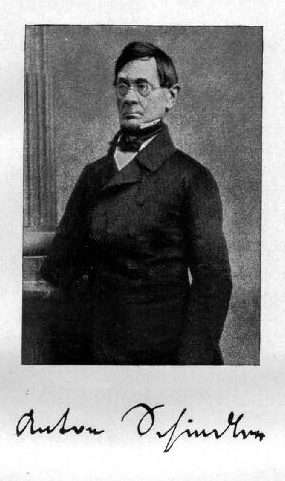

Volbach included a fine reproduction of the sole photograph of Schindler with a black cravat. As Schindler died in 1864, commercial photography was still in its early decades, which may explain the still expression on Schindler’s face. The photographer and date are unknown. The Beethoven-Haus website contains a copy of the photograph that was in the possession of Schindler’s great-niece Isabella Egloff, Munich, in 1917.

https://www.beethoven.de/s/catalogs?opac=bild_en.pl&t_idn=bi:i2659

As the founding director of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies from 1985 through 2016, I always kept my eye out for a copy of the card in the antiquarian market. None ever surfaced. The Beethoven-Haus collection, which dates back to the 1890s, does not contain a copy, nor does any library or collection. The non-existence of such a card is highly unlikely had it ever existed, as everything related to Beethoven, and especially in Beethoven-mad Paris of the 1840s and 1850s, would have been kept—at least one copy would exist. And as we see above, Schindler himself denied that he had printed it on a visiting card. Dr. Julia Ronge, curator of the Beethoven-Haus, and I have recently been communicating about the card that never existed. She herself researched it in the past by contacting the Heine-Haus in Düsseldorf, where an expert told her he was convinced the story was typical of Heine inventing such a joke when he mocked people.

I haven’t really wanted to check many modern biographies of Beethoven to see who is quoting Heine as if he had shared a fact about the visiting card. But one example suffices. In 2020 the University of California Press published an English translation of Jan Caeyers biography (Beethoven, A Life) from 2009 in which Caeyers repeats the Ami canard and and makes several other important errors about Schindler in his prologue (pp. xxi-xxii).

Conclusion: It’s time to purge Heine’s l’Ami de Beethoven lie from future Beethoveniana.

Thanks to: Dr. Julia Ronge, curator Beethoven-Haus, for her sharing of her research; Dr. Ted Albrecht, emeritus professor, Kent State University, for the exact dates of Schindler’s service as volunteer assistant; and Dr. John Wilson, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, for his information about Reicha and Pylades.