From the Collection of Kevin Brown, American Beethoven Society Corresponding Board Member.

A Brief Biography of Kevin Brown:

I am an honour’s graduate in Physics from the University of Newcastle (Australia) who has enjoyed a very successful business career and life, the latter due mostly to wonderful people I have met on my journey and one I have not whose name is Ludwig van Beethoven. I stumbled into Beethoven’s life accidentally on a flight to London in 1991 and the more I listened to his music, read of his life, the more intrigued I became to the point where now it is my passion.

I have been a member of the American Beethoven Society since 1999 and my involvement with the ABS has steadily increased over the years to becoming a Corresponding Board member in 2019.

Kevin Brown on Why He Became Involved and Supported the Project:

I first met Will Meredith in June 2010 at the Beethoven Center. His enthusiasm for Beethoven was similar to mine, and when he first mentioned the Beethoven DNA project in January 2015 that involved the Beethoven Center, the ABS, Tristan Begg at the University of Tuebingen, and Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute in Jena, my scientific background together with Beethoven’s wishes outlined in the Heiligenstadt Testament determined I needed to be part of the project. I wanted to support the project financially and professionally, especially in obtaining these locks of hair that would be the basis of the study. The goal was to sequence a high-quality genome from DNA extracted from authenticated hair samples originating from Beethoven and with modern research tools, better understand the numerous health issues he experienced during his life, particularly his deafness. It has been, at times, a frustrating adventure but overall, it has culminated in a significant positive for my life. (December 2022)

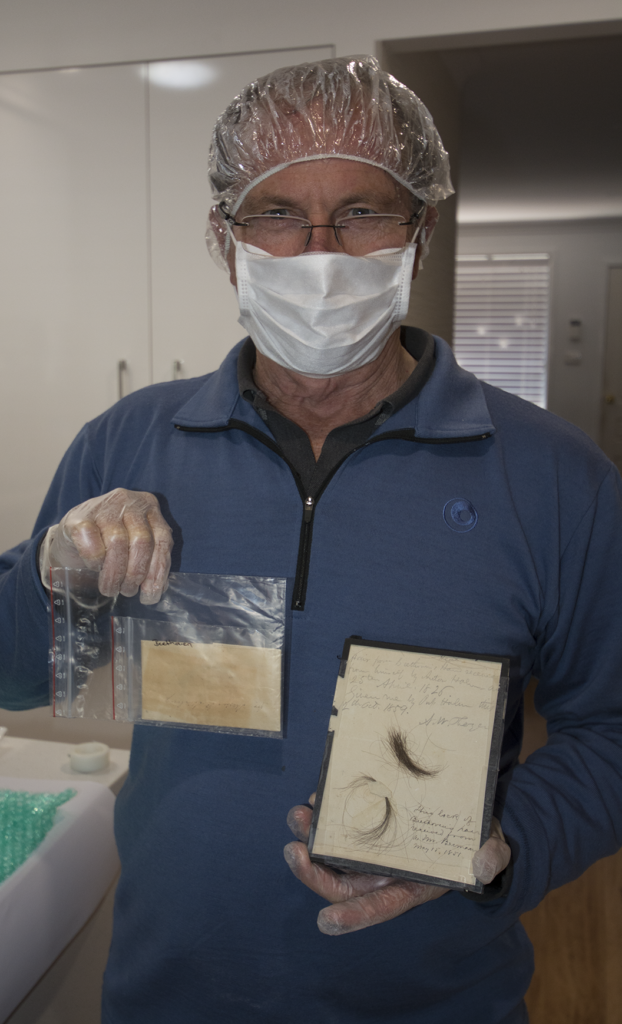

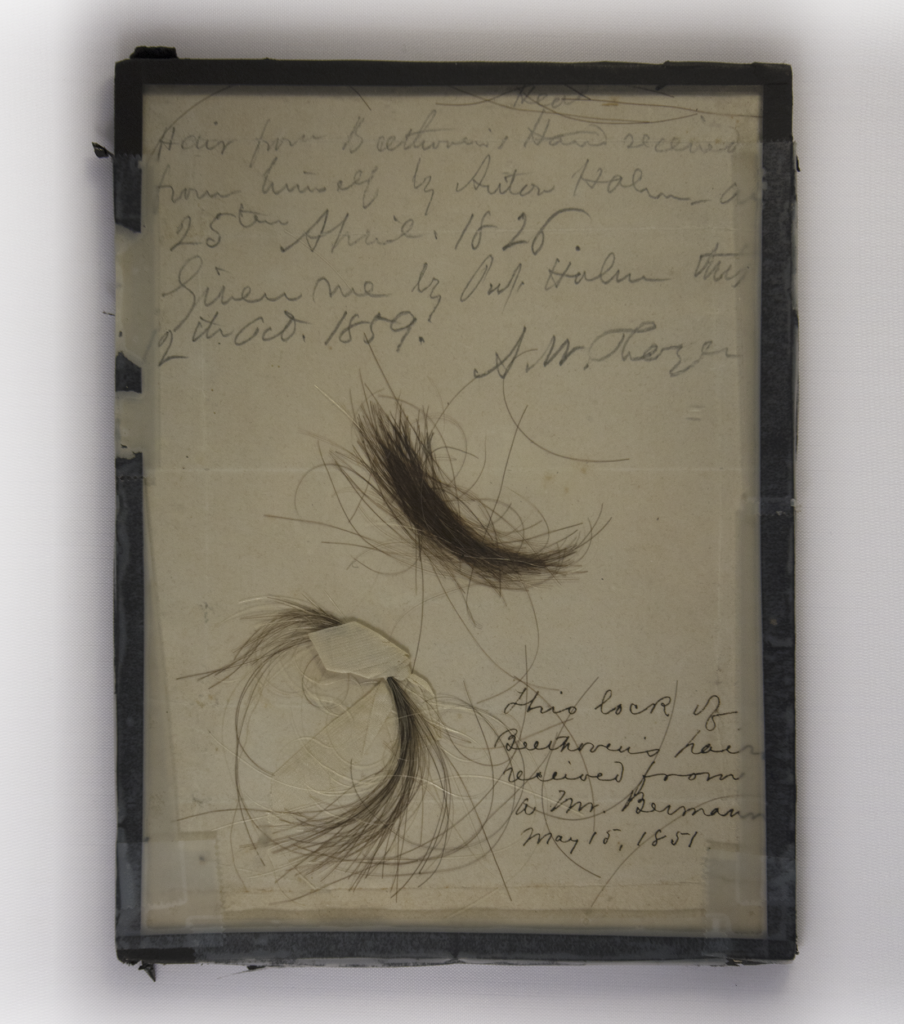

The Halm, Bermann, and Stumpff Locks of Beethoven’s Hair in the Kevin Brown Collection

The three locks in the Kevin Brown Collection are three of the five authenticated locks of Beethoven’s hairs detailed in the genome paper. The fourth authentic lock is at the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies (the Schindler-Moscheles Lock).

The fifth authentic lock is at the Beethoven-Haus, Bonn (the Streicher-Elise Müller Lock, HCB V 12).

https://www.beethoven.de/en/media/view/4686569352986624/

The Halm and Bermann Locks were given to the great American Beethoven scholar Alexander Wheelock Thayer and subsequently attached to a single piece of paper as seen in the photograph. After Thayer’s death, they—as well as many other items in his collection—remained in the family until they were sold to three members of the American Beethoven Society as the “Thayer Collection” in 2016 (Kevin Brown, William Meredith and Rafael Romo, and the Brilliant Family). Everything in the Thayer Collection except these two locks, which were paid for by Mr. Brown, was donated to the Beethoven Center by the remaining two donors. These items include one of Beethoven’s shirts that the children took to school for show-and-tell and Thayer’s uniform.

The two Thayer locks were purchased for use for the Beethoven Genome Project, which had been initiated in late 2014 by Tristan Begg and William Meredith. Mr. Brown purchased the Stumpff Lock at a Sotheby’s, London auction in November 2016 for research for the Beethoven Genome Project.

The Maria Halm Lock of Hair (provenance by William Meredith)

The story of the Maria Halm lock is the most extraordinary of all the stories about locks of the composer’s hair. Thayer himself, the careful Beethoven historian, documented the date of his receipt on the single framed page:

“Hair from Beethoven’s Head

Handreceived / from himself by Anton Halm on / 25th April, 1826. / Given me by Ant. Halm on / 12th Oct. 1859. / A.W. Thayer”

The story of what should properly be called the Maria Halm Lock is given in the fifth volume of Thayer’s biography of Beethoven, which was completed by Hermann Deiters from Thayer’s notes, further edited by Hugo Riemann, and published for the first time in 1908. The story appears on pp. 303-05:

“A mischievous joke took place during the time of the preparations for the performance of the Quartet in B-flat Major [Opus 130], which someone allowed himself with a lock of Beethoven’s hair. Concerning this matter, we have the own story [of the person], the keyboard player and composer Anton von Halm, who gave it to Thayer, which he recorded in his notes. On account of the same, Schindler’s story was in some part [confirmed] and completed. Halm’s wife, “born Sebastiani from Trieste, whom Beethoven always called his fellow countrywoman,” was also present at the rehearsal for Schuppanzigh’s concert (Trio in B-flat Major [Opus 97], Quartet in B-flat Major [Opus 130]. [prior to March 21, see below.] She had wanted to own a lock of Beethoven’s hair, a favor that few could boast about; Beethoven normally answered ‘Leave me alone!’ [‘Let me go].

[Halm speaking:] “With this favorable opportunity my wife requested that I ask Beethoven for a lock of hair. However, since Beethoven could not hear and several people were present, I decided to deal with the matter personally however through his conversation book [Notizsbuch]. I asked Carl Holz to carry the wish of my wife to Beethoven. In a few days my wife received through a third party a lock, which should have been Beethoven’s.”

[This occurred around March 31st (see the conversation book entry below). In the interim Beethoven asked Halm to arrange the fugue of the quartet for four-hand fortepiano.]

“In the meantime Carl Gross, a skilled dilettante on the cello, had said to me, ‘Who knows if the hair is authentic?’, but I had no doubt. When the arrangement was completed, I brought it to B.” and linked it with the earlier communicated conversation.

[The authentic hair cutting took place on April 25 (see the conversation book entry and the Halm letter below):]

Halm continued his story: “When I wanted to leave, he stepped towards me with a frightful seriousness on his face with the words: ‘You were deceived with the lock of hair! You see, I am surrounded with such frightful creatures who set aside all consideration that binds respectable people. You have the hair of a goat.’ And saying this, he gave me in a white sheet of paper a significant quantity of his hair, which he had himself cut entirely backwards, with the words: ‘That is my hair!’ [‘Das sind meine Haare!”] —Probably he had cut the hair from the back because it was still dark there, while in the front it was already snow-white. — So I went home in triumph having received this rare gift. — Not so my wife. She was indignant with Carl Holz about his dirty trick, wrote someone immediately about the circumstances appropriate letter. One or two years later my wife stood over the open grave of Beethoven [on] March 29, 1827. — and saw Holz on the other side standing and crying, who could not look at her out of shame. Thereby she deigned to extend the hand of reconciliation over the grave. —”

(Translation by William Meredith)

Beethoven’s volunteer secretary Anton Schindler published two versions of the Halm story that are inaccurate in some details. In the first edition of his biography of Beethoven that appeared in 1840, he told the story in this fashion:

“The wife of M. H—m, an esteemed piano-forte player and composer, residing in Vienna, was a great admirer of Beethoven, and she wished to possess a lock of his hair. Her husband, anxious to gratify her, applied to a gentleman who was very intimate with Beethoven, and who had rendered him some service. At the instigation of this person, Beethoven was induced to send the lady a lock of hair cut from a goat’s beard; and Beethoven’s own hair being very gray and harsh, there was no reason to fear that the hoax would be very readily detected. The lady was overjoyed at possessing this supposed memorial [Reliquien] of her saint, proudly showing it to all of her acquaintance; but, when her happiness was at its height, some one, who happened to know the secret, made her acquainted with the deception that had been practiced on her. In a letter addressed to Beethoven, her husband warmly expressed his feelings on the subject of the discovery that had been made. Convinced of the mortification which the trick must have inflicted on the lady, Beethoven determined to make atonement for it. He immediately cut off a lock of his hair, and enclosed it in a note, in which he requested the lady’s forgiveness of what had occurred. The respect which Beethoven previously entertained for the instigator of this unfeeling trick was now converted into hatred, and he would never afterwards receive a visit from him. This is not the only instance that could be mentioned, in which our great master was influenced by vulgar-minded persons to do things unworthy of himself.”

(This is the English translation of the biography that appeared on pp. 180-82 of vol. 2 in 1841. See The Life of Beethoven Including His Correspondence with His Friends, Numerous Characteristic Traits, and Remarks on His Musical Works, ed. Ignace Moscheles, 2 vols. London: Henry Colburn, 1841. It appears on pp. 262-63 of the original German edition of 1840: Anton Schindler, Biographie von Ludwig van Beethoven, Münster: Aschendorff’schen Buchhandlung, 1840.)

When he revised the biography for the third edition in 1860, Schindler revealed Halms’ name:

“We promised our readers an example of our master’s disposition, despite his misfortunes and frequent ill-humour, towards buffoonery and practical joking. The wife of Halm, the pianist and composer, wanted a lock of Beethoven’s hair. The request was made through Karl Holz, who persuaded the master to send his ardent admirer some hairs from the beard of a goat, actually not too different from Beethoven’s own coarse grey hair. The lady, delighted with this memento of her musical ideal, boasted far and wide of the gift, but before long she learned how she had been duped. Her husband was still deeply sensitive of his honour as a military officer, and in an aggrieved letter to our master related what he had heard. When Beethoven realized that his prank had been taken as an insult, he atoned for it by cutting off a lock of his own hair and sending it to the lady with a note begging for forgiveness. The incident occurred in 1826.”

(Translation from Anton Schindler, Beethoven as I Knew Him, A Biography, ed. Donald W. MacArdle, trans. Constance S. Jolly, London: Faber and Faber, 1966, pp. 383-84. Translation of the 1860 edition.)

The story is documented in part in several conversation book entries and Halm’s letter to Beethoven of April 24, 1826. However, there are two important details that Halm did not know and Schindler misrepresented, in part because of apparent ignorance. First, there is no evidence that Holz persuaded Beethoven to send her the lock of hair; Holz gave it to her, according to his own words. Second, around March 31, Holz had already told Beethoven that he had sent Maria Halm the lock, so it was probably Holz who dreamt up the scam. Thus, Beethoven must have been pretending to Halm that he had not known about Holz’s scam when he spoke to him on April 25, because he had been told a lock had been given around March 31.

- Around March 5: Carl Holz writing to Beethoven in Conversation Book 105, 63v, about the rehearsal of the String Quartet in B-flat Major, Opus 130: “Ich probire mit My- / Lord das Quartett” (“I am rehearsing with My- / Lord [Schuppanzigh] the Quartet”) (Ludwig van Beethovens Konversationshefte, ed. Grita Herre and Günter Brosche, 11 vols., Leipzig: VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, 1988, p. 9:92)

- Between March 5-11: Carl Holz writing to Beethoven in Conversation Book 106, 17r, about a rehearsal: “Wir haben von 6 bis 10 / Uhr probirt.” (We rehearsed from 6 until 10.” (Konversationshefte, vol. 9, p. 104)

- Between March 5-11: Carl Holz writing to Beethoven in Conversation Book 106, 17v, about Halm playing the Archduke Trio: “Halm wird auch Ihr / B Trio spielen.” (“Halm will also play the Trio in B-flat Major”)

(Konversationshefte, vol. 9, p. 104)

On March 21 the violinist Schuppanzigh presented a concert with the Quartet in B-flat Major with the Grosse Fuge, Opus 133, as the finale and also the Archduke Trio with Anton Halm, fortepiano; Schuppanzigh, violin; and J. Linke, cello.

- Around March 31: Carl Holz writing to Beethoven in Conversation Book 107, 23r, about sending the lock to Halm: “Der Halm habe ich schon / die Haare geschickt.” (“I have already given the hair to Halm.”) (Konversationshefte, vol. 9, p. 130)

- April 16: Anton Halm writing to Beethoven in Bk. 108, 24v: “Meine Frau dankt höf- / lichst für das theure / Andenken die Haare als Landsmän / nin, und wen wir nicht / lasting sind, werden wir / [spr]zusammen unsern / Besuch abstatten” ([Apr. 16th] (“My wife respectfully thanks you for the precious souvenir as a countrywoman and if we are not tiring, we will call on you together for a visit”) (Konversationshefte, vol. 9, p. 193)

- April 24: Letter of Halm to Beethoven dated April 24 stating that he is sending along with the letter his arrangement for fortepiano, four-hands, of the Grosse Fuge: “I shall take the liberty of delivering your manuscript at a quarter past three tomorrow afternoon, at the latest, to get your kind opinion of my arrangement.” (Letters to Beethoven and Other Correspondence, trans. and ed. Theodore Albrecht, 3 vols., Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1996, vol. 3, p. 137, Albrecht letter no. 431.)

The Bermann Lock of Hair (provenance by Tristan Begg and William Meredith)

The Bermann lock is affixed to the same piece of paper as the Thayer-Halm lock. It is identified in this manner:

“This lock of Beethoven’s hair received from a Mr. Bermann. May 15, 1851.”

The history of the lock is unknown, although it most probably originated from Jeremias Bermann (1770-1855), who had married Anna Eder (1790-1859), the daughter of the publisher of four of Beethoven’s early compositions, Joseph Eder (1759-1855). The two most significant of the Josef Eder’s editions are the first edition of the three Fortepiano Sonatas, Opus 10, and the first Titelauflage (reprint edition) of the Pathétique Sonata, Opus 13. Bermann joined his father-in-law’s firm in 1811 and took over operations of the music and art dealership in 1815. The firm’s specialty was the printing of visiting cards and New Year’s cards. The Edersche Kunsthandlung was in a building called “Zum schwarzen Elephanten” (Black Elephant) on the famous Graben street.

https://www.dorotheum.com/de/l/5148265/

In June 1821 Jeremias Bermann published the first edition of Beethoven’s Bagatelles, Opus 119, nos. 7-11, as part of the third volume of the Wiener Piano-Forte-Schule von Frd. Starke, Kapellmeister. The manuscript of no. 7 is dated “am 1=ten Jenner 1821.” That date helps us locate Bermann’s direct connection to Beethoven to between late 1820 and the early summer of 1821. Unfortunately, there is a gap in the conversation books of Beethoven from 1820-22, and Bermann is not mentioned in any of the surviving books. Bermann is also not mentioned in any Beethoven letter. Thus, while we know Bermann had a direct connection to the composer in 1820-21, there is no surviving document, besides the note on this lock of hair, connecting them or telling how or when Bermann acquired the lock. It apparently stayed in his collection until 1851 when he gave it to Thayer.

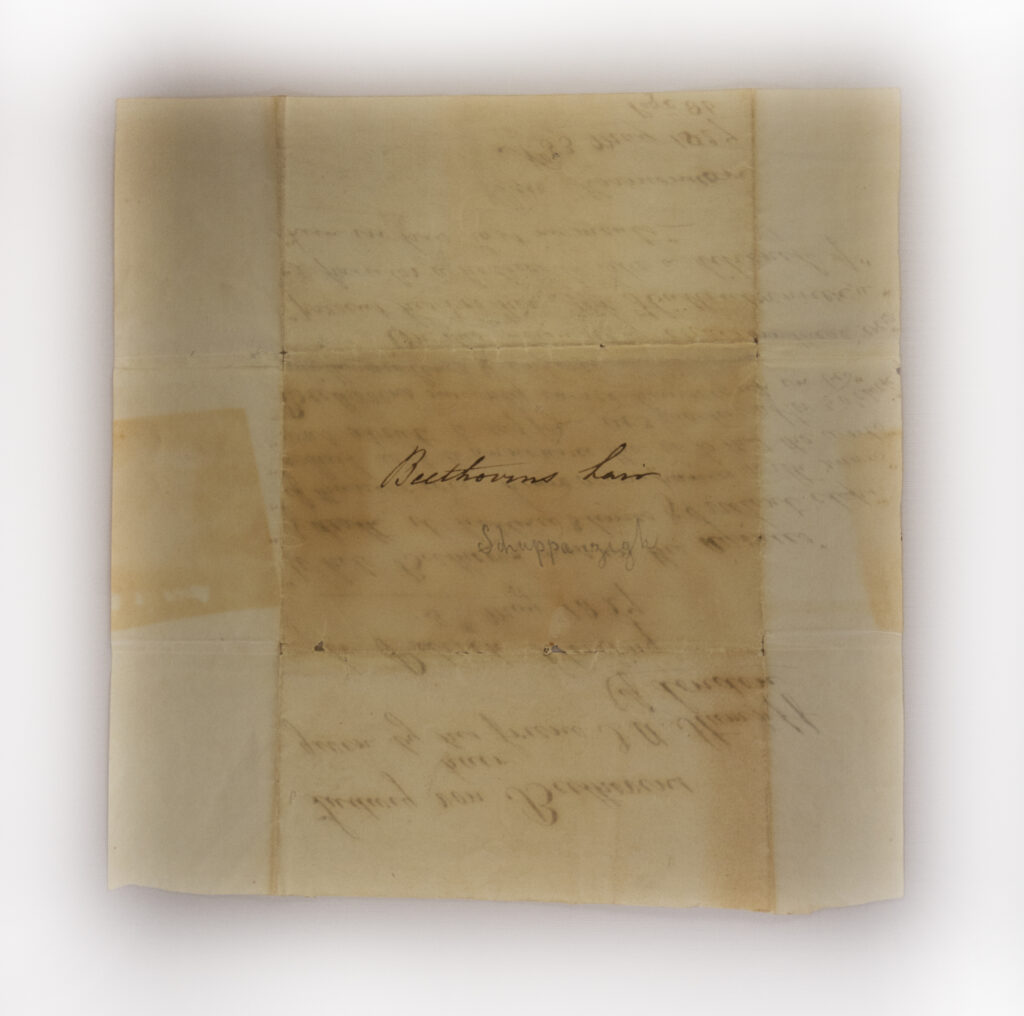

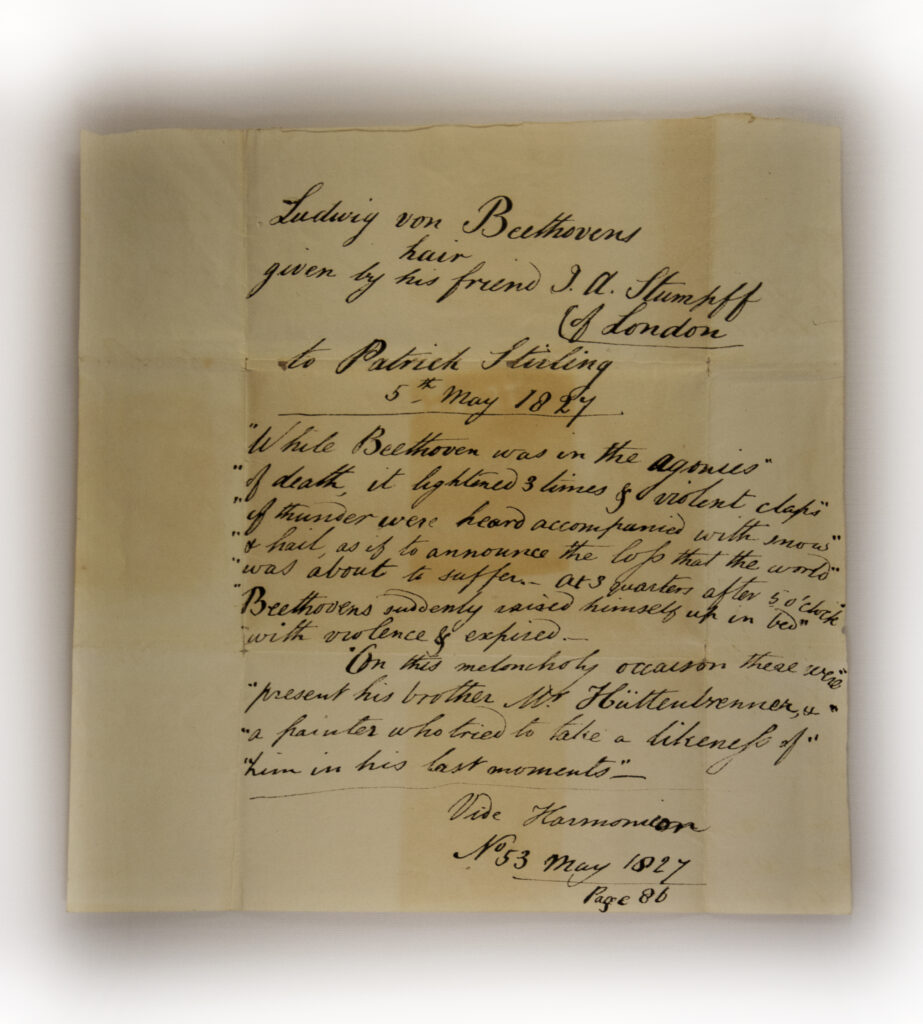

The Stumpff Lock of Hair (provenance by Tristan Begg)

The Stumpff Lock has well-documented provenance between March 28, 1827, and May 7, 1827, but disappears from the historical record for nearly two centuries until its resurfacing in November 2016 when it was auctioned at Sotheby’s, London. The lock was originally sent to London-based Thuringian-born harp maker Johann Andreas Stumpff (1769-1846) on March 28, 1827, in a letter written by a mutual friend of Stumpff and Beethoven, Johann Baptist Streicher (1796-1871), the son of Beethoven’s close friend Nannette Streicher (see below). Also included in this letter was a small sheet of music manuscript, both items being sent to Stumpff by Streicher on behalf of Johann Valentin Schickh (1770-1835), who was taking responsibility for Beethoven’s funeral at that time and was too busy to write. The hairs were therefore first acquired at some point between Beethoven’s death on March 26 and Streicher’s sending of the letter on March 28, 1827. Below is the text of Streicher’s letter to Stumpff of March 28, 1827, relating to the hair and music manuscript:

“Since Herr Schickh has eagerly taken responsibility for Beethoven’s funeral, he is prevented at the moment from writing to you and Herr Schultz himself. Meanwhile, he sends you the enclosed lock of Beethoven’s hair, cut after his death, as well as a little piece of manuscript; a larger will follow.”

(Letters to Beethoven and Other Correspondence, trans. and ed. Theodore Albrecht, 3 vols., Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1996, vol. 3, p. 206, Albrecht letter no. 472.)

This correspondence was, along with the letter of Schindler to Moscheles from four days before, reproduced in the same volume of Harmonicon that announced Beethoven’s death. Stumpff then acknowledges receipt of the hair and music shortly after receiving them in a letter sent to Streicher on April 16, 1827:

“The passing of that irreplaceable great German man, our friend Beethoven, pierced me deeply. Here I sit, bent over your dear letter that confirmed the news of it for me, and stare at the lock that adorned the head from which flowed the immortal works, which are and shall remain the admiration of all cultivated nations. … Now, my dear friend, I thank you most sincerely for the lock of hair and music of our departed friend that you sent, with the request that you give Herr von Schickh my many regards, and extend my thanks for the tender proof of his friendly sentiments toward me.”

(Letters to Beethoven and Other Correspondence, trans. and ed. Theodore Albrecht, 3 vols., Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1996, vol. 3, p. 225, Albrecht letter no. 480.)

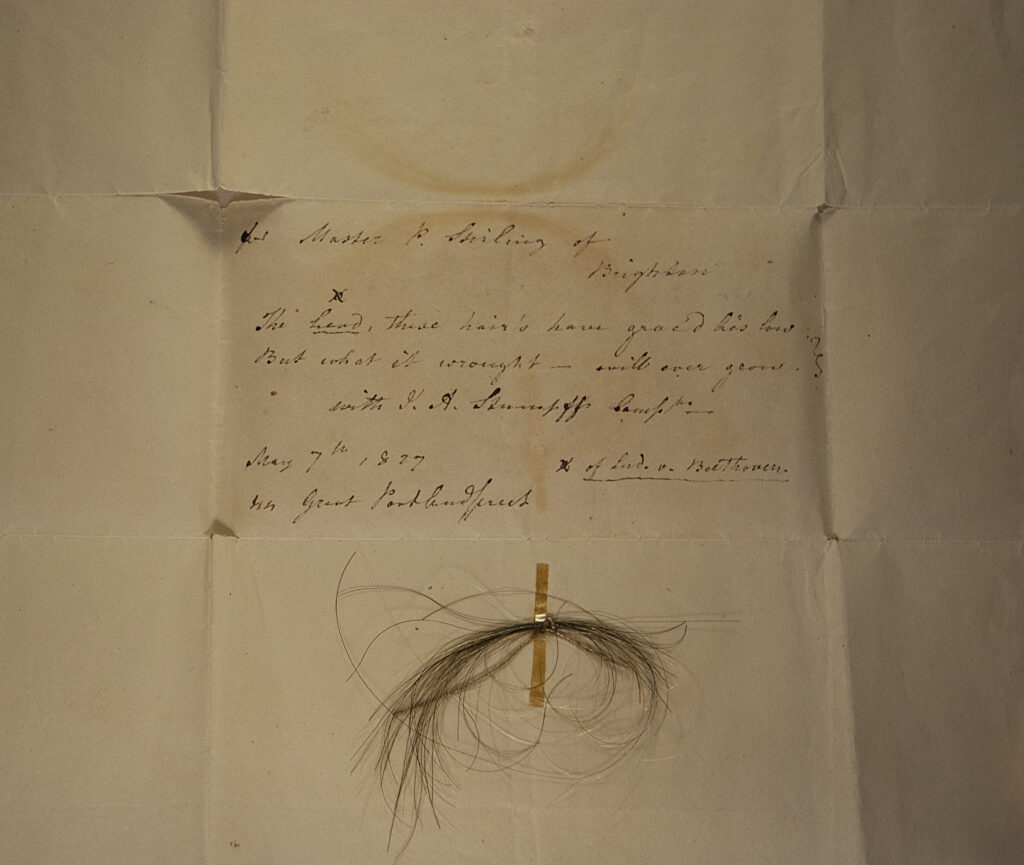

The lock next appears affixed to a letter from Stumpff to the thirteen-year-old orphan and inheritor of the Scottish Stirling clan estates, Patrick Stirling (1813-1839). The letter contains two notable features idiosyncratic of Stumpff’s correspondence, one of which being a short poem, and the other being Stumpff’s tiny handwriting. The text of this letter is reproduced below:

For Master P. Stirling of

Brighton

X

The head, these hair’s have grac’d lies low

But what it wrought – will ever grow. }

with J. A. Stumpff Compts –

May 7th, 1827 X of Lud. v. Beethoven.

44 Great Portland Street

It is not yet clear what prompted Stumpff to send these hairs to the orphan Patrick Stirling, although it is interesting to note that Patrick Stirling’s aunt, Jane Stirling (1804-1859), would become one of Frédéric Chopin’s (1810-1849) patrons and tutees in Chopin’s later years. A detail worthy of mention consistent with an origin for the hairs in early nineteenth-century Vienna can be found on the paper in which the Stumpff Lock was originally folded. On one side is penned in dark ink “Beethovens hai’r, and on the other side is lightly penciled the name ‘Schuppanzigh‘ in a separate hand. Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776-1830) was a close associate of Beethoven, having premiered many of his string quartets and the Ninth Symphony as first violinist.

The Stumpff Lock was acquired by American Beethoven Society member Kevin Brown at auction in late November 2016 for analysis in the Beethoven Genome Project. Two extractions each consisting of 25 cm, or four hairs, were initially performed for authentication purposes, amounting to a total of 50cm or 8 hairs removed from the lock. Subsequently, the Stumpff Lock was chosen, owing to superior DNA preservation for further extractions to generate libraries, for production sequencing of a high-coverage genome. An additional 56 hairs amounting to 275cm were removed and destructively sampled in 11 additional extractions. The Stumpff Lock is part of the collection of American Beethoven Society member Kevin Brown.