Of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies and the American Beethoven Society (1994-2014)

A Summary Report by Dr. William Meredith, emeritus director,

The Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies (1985–2016)

Project Chair: William Meredith, Beethoven Center

Abstract:

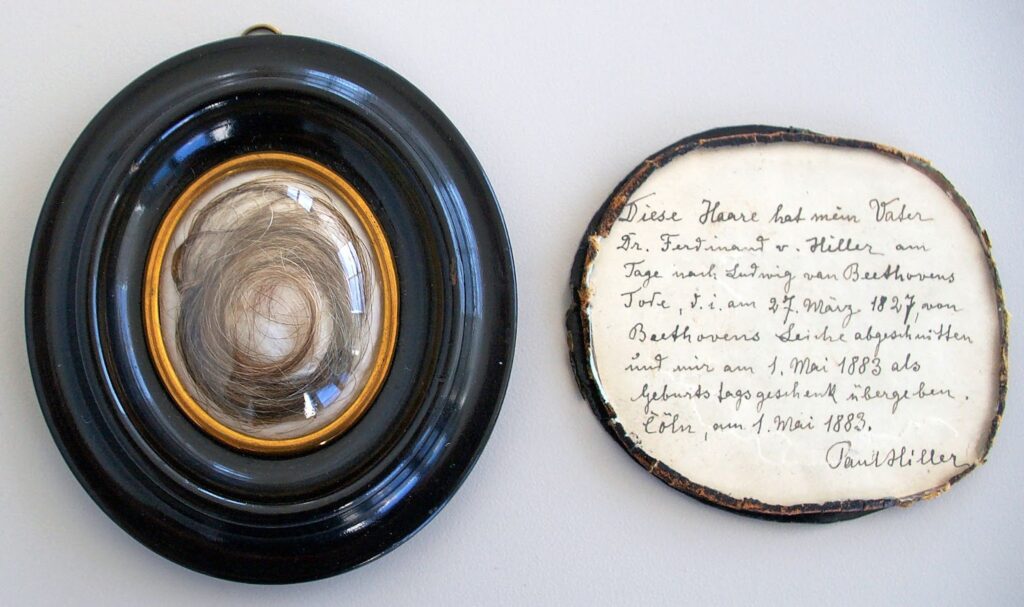

In 1994 four members of the American Beethoven Society purchased a lock of hair at an auction at Sotheby’s, London, that was said to have come from Beethoven. When the lock arrived in the United States, a small committee was formed to proceed with the Ferdinand Hiller Lock Authentication Project, because the committee wanted to make strands of the locks available for scientific research to see what could be discovered about the composer’s health. A number of research projects followed, but the DNA in the hair could not be analyzed because the field of extracting “ancient DNA” from hair had not yet advanced to the stage where it was possible and genomic sequencing was not yet possible. (Next Generation Sequencing would not become available for at least another ten years.) Part of the Hiller Authentication Project involved the successful search for three fragments of a skull that had been stated as coming from Beethoven in a book published by two Viennese pathologists in 1987.[1] Material from one of these fragments was also tested for genetic material, but the meager results were similarly incomplete and inaccurate. The amazing history of the provenance of the Hiller lock of hair was written by Russell Martin, whose book Beethoven’s Hair was published in 2000 by Broadway Books, New York. A documentary film of the same title was produced in 2005 that also contained advanced testing of one of the bone fragments. In 2012 it was discovered, however, that the skull fragments could not have come from Beethoven’s skull for morphological reasons.

(PHOTO CREDIT: William Meredith; permission to reprint this photo must be obtained from the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University)

Because advances in genomic testing had made great strides since the Hiller Project began, in 2014 Tristan Begg approached me as director of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies and the Executive Director of the American Beethoven Society to inquire if the Center and Society would allow for samples from its locks supposedly from Beethoven to be studied based on these advances in genomic research. I readily agreed, as we did not want to display locks if they were not authentic. Meanwhile, a longtime ABS board member, Kevin Brown, joined the team and helped acquire three additional locks for analysis. By October 2016 Tristan Begg discovered, as part of his Masters work in Archaeological Sciences, focusing on Paleogenetics, at the University of Tübingen, that the Hiller Lock was also not from Beethoven, but most likely from a Jewish woman of Ashkenazi heritage. Thus, according to scientific experts, any results obtained from the Hiller Lock and the bone fragments do not relate to Beethoven. The American Beethoven Society continued to support the ongoing project that has resulted in the new release of data on Beethoven’s genome. That report was the result of a collaboration among thirty-two researchers and historians at Cambridge University, the Max Planck Institute, the University of Leuven, the University of Bonn, the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies at San José State University, FamilyTreeDNA, and the Beethoven-Haus. As of 2022, the American Beethoven Society has contributed $176,000 in grants towards this research.

Collaborators and Contributors

- Ira F. Brilliant, SJSU Beethoven Center founder, Phoenix, Arizona

- Dr. Alfredo Guevara, urologist, Nogales, Arizona

- Dr. Thomas Wendel, then president of the American Beethoven Society, Campbell, California

- Caroline Crummey, American Beethoven Society member, San José, California

- Russell Martin, author of Beethoven’s Hair (published in 2000 by Broadway Books, New York)

- Paul Kaufmann, businessman, Danville, California

- Kevin Brown, ABS Executive Board, ABS member since 1999

Scientists

For hair non-DNA tests:

- Dr. Werner Baumgartner, head, Psychemedics Corporation, Culver, California (hair radioimmunoassay, 1996)[2]

- Dr. Walter McCrone, McCrone Research Institute, Chicago (hair scanning electron microscope energy dispersion spectronomy, SEM/EDS, and scanning ion microscope mass spectrometry, SIMS, 1997)[3]

- Dr. William Walsh, Health Research Institute, Napierville, Illinois (hair trace-metal analysis, 1996-2000)[4]

- Ken Kemner, Environmental Research Division, Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (2000) (the Argonne tests are documented in the film Beethoven’s Hair)

- Francesco Di Carlo, Experimental Facilities Division, Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (2000)

- Derrick Mancini, Experimental Facilities Division, Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (2000)

- Dr. Christian Reiter, Zentrum für Gerichtsmedizin (Department for Forensic Medicine), Medizinische Universität Wien (2007, 2021)[5]

For genetic testing (these results were only communicated to the owners in brief reports whose contents are contained below):

- Dr. Marcia Eisenberg, LabCorp of America, Research Triangle Park (PCR and Sanger Sequencing based analysis of hypervariable regions I and II of the mitochondrial genome, 1999)

- Dr. Bernd Brinkmann, Director, Institute of Legal Medicine, Münster University (bone fragment DNA analysis, 2005), with Dr. Carsten Hohoff, Münster University

For skull fragment lead test:

- Dr. Andrew Todd, School of Medicine, Mt. Sinai, New York (2010)[6]

Please note: For more information on some of the scientific tests listed above, please see (1) Russell Martin’s book Beethoven’s Hair, (2) the movie Beethoven’s Hair (produced in 2005 by the BBC, CBC, and the Canadian Television and Cable Production Fund License), and (3) information on the web. Martin’s book does not contain an index, so I have provided page numbers in the endnotes on the studies listed above.

For osteology identification tests (all of these are discussed in an article cited below):

- Dr. Timothy White, University of California, Berkeley (osteological examination of fragment, February 17, 2012)

- Dr. Mark Griffin, Bioanthropology Laboratory, San Francisco State University (June 2012)

- Dr. Patrick Willey and Dr. Eric Bartelink, Human Identification Laboratory, California State University, Chico (July 2012)

- Dr. Alison Galloway, Forensic Osteological Investigations Laboratory, University of California, Santa Cruz (August 2012)

Summary:

As noted below in the history of the Hiller Authentication Project, the two samples that were studied—the Hiller lock of hair and two of the three Adalbert Seligmann bone fragments—were subsequently proven not to have come from Beethoven. The two bone fragments were publicized and misidentified in 1987 by two Viennese doctors at the University of Vienna (Dr. Hans Bankl and Dr. Hans Jesserer) but found to be unauthentic in February 2012 through analysis by Dr. Timothy White, University of California, Berkeley, a finding that was subsequently confirmed by four osteologists in the summer of 2012. (The remaining large fragment, a piece of occipital bone, cannot be ruled out on the basis that it would have been “bisected by the autopsy report,” according to Dr. Galloway, but its appearance suggests that it could have come from the same skull.) The Hiller Lock was found to be unauthentic during the new Beethoven Genome Project in 2016 by Tristan Begg, then earning his masters in Archaeological Science, focusing in Paleogenetics, at the University of Tübingen. The analysis of the Hiller Lock was part of the larger project’s work on authenticating Beethoven’s genome by testing eight samples purportedly said to have come from Beethoven.

Thus, all the evidence obtained from testing strands from the Hiller Lock and the Seligmann fragment, including the finding that Beethoven suffered from lead poisoning, relate not to Beethoven but to other individuals.[7]

It is critical to note that all of the research on the Hiller lock and Seligmann bone fragments was done in good faith before the lock of hair and bone fragments were discovered to be from someone other than Beethoven.

History:

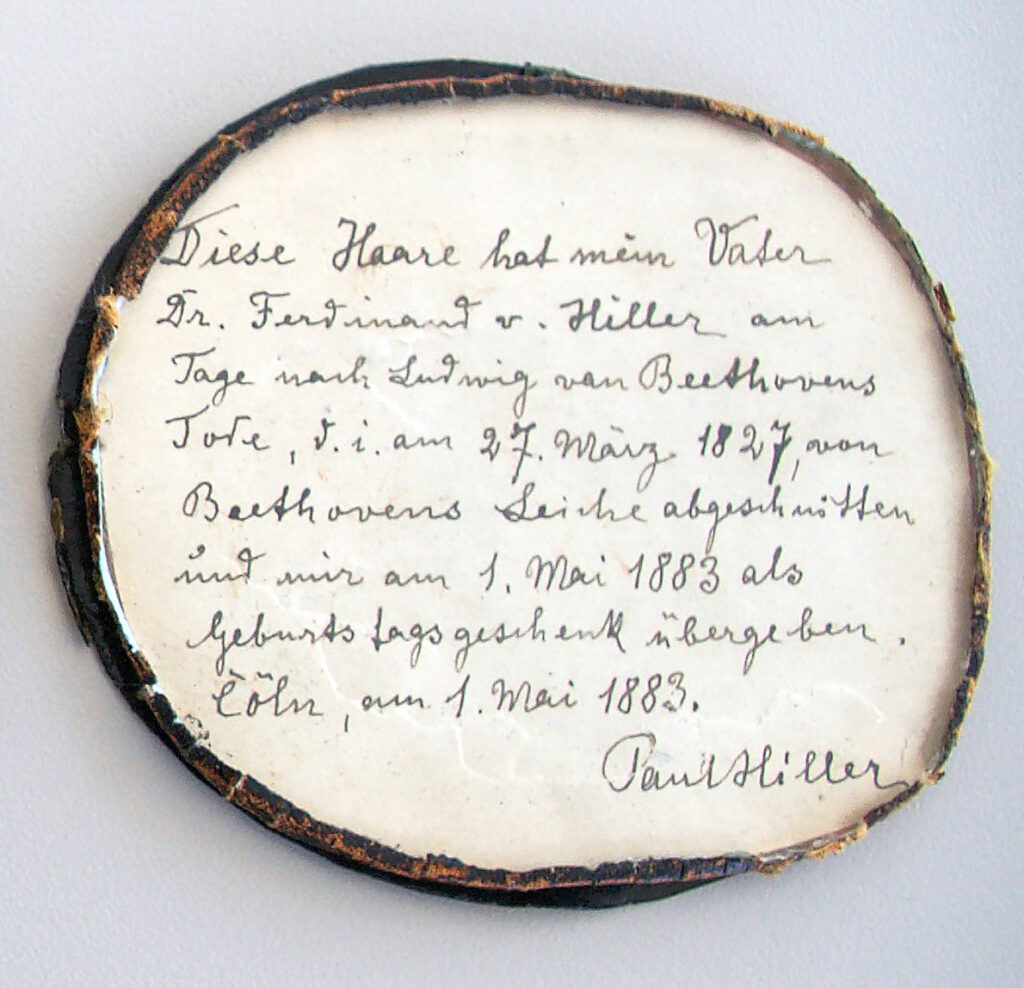

In December 1994 Sotheby’s, London, held an auction with the sale of a lock of hair that was claimed to be from Beethoven. It had first been offered to the Christie’s auction house office in Copenhagen in the late 1970s, but the owner (Marta Fremming) was told that, even if the lock was authentic, the value would be “quite small.” The lock was in a small oval black frame and contained an attestation underneath glass on the back that (1) it had been cut from Beethoven’s head the day after his death by Ferdinand Hiller (1811–1885), who was visiting Beethoven with his teacher Hummel, and (2) that it was subsequently given to Paul Hiller, Ferdinand’s son, on May 1, 1883, for his thirtieth birthday. In April 1994 a second attempt to sell the lock was made at the Sotheby’s office in Copenhagen, which passed on the information to the London office. Stephen Roe, then head of the Books and Manuscripts Department, believed the lock was authentic because its wooden frame was consistent with early 19th-century German frames and the fact that it was well documented that Hiller had made several visits to Beethoven when he was on his deathbed and afterwards. He offered to include it in the December auction of “Music and Continental Books.” The hair became lot 33 in the December 1 auction, where it was purchased by antiquarian dealer Richard Macnutt for 3,600 pounds ($5,640, not including fees), somewhat above the estimate of 2,000-3,000 pounds, on behalf of four members of the American Beethoven Society.

(PHOTO CREDIT: William Meredith; permission to reprint this photo must be obtained from the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University)

(Photo credit: William Meredith; permission to reprint this photo must be obtained from the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University)

In November 1994 William Meredith, then director, and curator Patricia Stroh had received advance notice of the Beethoven pages of the sale and discussed bidding on the lock with the founder of the Center, Ira F. Brilliant, who had already decided to put the bulk of his funding behind a bid to acquire a first edition of Beethoven’s Fortepiano Trios, Opus 1, in the auction. The goal was to obtain a lock of the composer’s hair for display at the Beethoven Center. Ira Brilliant and three other members of the American Beethoven Society contributed funds for a bid, which was successful. A negotiation ensued between Mr. Brilliant and Dr. Guevara in which it was agreed that the majority of the hairs would come to the Center and that Dr. Guevara, who contributed the bulk of the funding, would receive the remainder for his private collection and for samples for research. The other contributors were Ira Brilliant, Dr. Thomas Wendel, and Caroline Crummey. The locket was opened under sterile conditions in Arizona in December 1995, the strands of hair were counted (including the number of hair follicles), and it was discovered that the piece of paper documenting the hair was a copy of the original paper, of which only a burned partial fragment remained (ostensibly in Paul Hiller’s handwriting).

Even before the lock arrived in the United States in early 1995, Mr. Brilliant and Dr. Guevara began to try to understand how the strands of hair could help us understand the composer’s medical history. The plan was two-fold: (1) to allow researchers to study strands of the lock from Guevara’s portion of the hair and (2) to try to confirm that the lock was authentic by comparing its DNA to another sample of the composer’s DNA. (Details of their discussions and plans and the known provenance of the lock—and the missing gaps—are richly detailed in Russell Martin’s Beethoven’s Hair.)

The genome research was facilitated when Martin used funds from his advance for Beethoven’s Hair to hire a private investigator in France to find what had been described as three small fragments of Beethoven’s skull. If they could be located, a comparison could be made between the Hiller Lock and the skull fragments. Two doctors in Vienna, Hans Bankl (1940–2005, professor of pathological anatomy) and Hans Jesserer (1914–1999, internal medicine), had examined and identified the fragments as coming from Beethoven’s skull in a book that appeared in 1987 (Die Krankheiten Ludwig van Beethovens: Pathographie seines Lebens und Pathologie seiner Leiden; The Illnesses of Ludwig van Beethoven: Pathography of his Life and Pathology of his Suffering). The private investigator discovered that the fragments had been inherited by Paul Kaufmann, a businessman who lived in Danville, California (approximately forty-two miles from the Center), along with many other objects coming from the collection of his great-uncle, Adalbert Seligman (1862–1945), a famous painter and artist. Seligmann said he had inherited the fragments from his father, the famous Viennese doctor Romeo Seligmann (1808–1892), who had been a member of Schubert’s circle of acquaintances and who had studied Beethoven’s skull fragments in 1863 when the skeleton was exhumed the first time. Kaufmann, himself curious about the authenticity of the fragments, graciously agreed to cooperate in the DNA research in 2000.

I began a years-long study of the correspondence, documents, and art inherited by Mr. Kaufmann to discover and document the history of these fragments in as much detail as possible.[8] Unfortunately, the single most important document, a letter of some kind of attestation from Dr. Hermann Welcker, professor and director of the Anatomical Institute of the University Halle from 1876-1893, was missing from the Kaufmann Family Archives. (It went missing between 1945, when Tom Desmines—Paul Kaufmann’s uncle—took possession of the small oval shaped box that contains the fragments, and 1970.)

The first DNA test of three strands of the Hiller lock, consisting of a PCR and Sanger Sequencing based mitochondrial DNA analysis, was conducted by Dr. Marcia Eisenberg and her team at the Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, location of LabCorp of America. The sample of three hairs was delivered on January 22, 1999, and the “Certificate of Analysis” was sent to Dr. Guevara on June 18, 1999. According to Dr. Eisenberg’s test, the sample was very difficult to obtain any results from, and the lab discovered only three differences from the Anderson Sequence in their PCR test. Her analysis, which was not confirmed in the subsequent Beethoven Genome Project that began in 2014, follows:

“Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) isolated from the above listed evidence was characterized through the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by sequencing of the hypervariable region (HV-1) and region II (HV-2) of the mitochondrial genome. The sequence obtained from the hair at NV1 exhibited no differences when compared to the Anderson sequence. The following differences from the Anderson sequence was noted at HV2:

Base Cell HV-2

Item Sample 73 263 315.1

Anderson Sequence A A —

22 Hair A(G) G C

— = Denotes insertion or deletion compared to the Anderson sequence

( ) = Denotes heteroplasmy at this location or a mixture”

The DNA test of the Kaufman bone fragments (a quantitative polymerase chain reaction test for nuclear DNA, followed by the same PCR and Sanger Sequencing approach) took place in late June and early July of 2005 by Dr. Bernd Brinkmann, forensic pathologist and then director of the Institute of Legal Medicine, Münster University. The Kaufmanns and I traveled to Germany to deliver the fragments; Paul Kaufmann approved the removal of interior material from one of the larger fragments for the test. Brinkman reported his data to Kaufmann, who shared the results with me so that we could compare them with the Eisenberg results. Brinkman’s analysis also was not confirmed in the subsequent Beethoven Genome Project, follows.

Though neither investigating DNA team was satisfied with the results that could be obtained at the time, the partial reports indicated that the hair and the fragments were or could be a match (according to information communicated to Paul Kaufmann). Accordingly, my report on the provenance of the fragments, begun in 2000, was finally published in The Beethoven Journal in 2005 as “The History of Beethoven’s Skull Fragments: Part One” (vol. 20, nos. 1 & 2, pp. 2–46).

In January 2012 I asked Paul Kaufmann if we could have the much smaller fragments of bone in the same small oval metal box examined by an osteologist. (Paul’s mother had described them in a letter as “ear bones.”) He agreed, and we were fortunate that Dr. Timothy White at the University of California, Berkeley, a world-renowned paleoanthropologist and Professor of Integrative Biology, agreed to do so. At a meeting on February 17, 2012, the two fragments glued back together were examined both by Dr. White and students in his upper division human osteology class. Dr. White identified the bones as coming from the right frontal bone and concluded that they therefore could not be from Beethoven because they would show marks of being cut through during the craniotomy that was part of his autopsy. Dr. White told us that the standard procedure in such examinations is to send casts of bone pieces in question to other osteologists for their opinions. In this case, Kaufmann allowed me to carry the pieces to four other renowned California osteologists in the summer of 2012. All agreed that the glued pieces were frontal. (Although he did not have time to study the smaller pieces in the metal box, Dr. White stated that they probably were pieces that had broken off the larger pieces.) Their results were published in my “The History of ‘Beethoven’s’ Skull Fragments: Part Two,” The Beethoven Journal.[9]

Thus, at the end of the Hiller Authentication Project in 2012, it was clear that the bone samples did not come from Beethoven, and it appeared that genome analysis of hair samples would have to wait until the field of analyzing what is called “ancient DNA” had sufficiently progressed. The Society had, however, continued to acquire two additional locks of hair for such a purpose that it donated to the Center.

So much progress had been made by 2014 that I was approached by Tristan Begg, who inquired if I would permit, as director of the Beethoven Center, for samples to be taken from locks of hair that the Center owned. The collaboration that began with Begg, myself as director, and the Society eventually resulted in a team that grew over the years to include many international geneticists, medical genetic specialists, and music historians in the new Beethoven genome project.

Knowing that the genome project would need more samples for testing, I began to work with Kevin Brown, New South Wales, Australia, and other members of the American Beethoven Society to acquire additional samples beyond the two the Center already owned that could be evaluated. In April 2015 the Society acquired strands of hair that were described as coming from the Cramolini family (these were gifted to the Center). In November 2016 Brown acquired the Stumpff Lock at a Sotheby’s, London, auction. In July 2017 three members of the Society purchased the Thayer Collection, which contained two locks of Beethoven’s hair (one from Halm and one from Bermann; the majority of the funds were supplied by Brown, who paid for the two locks). The three locks remain in Brown’s possession so that they may be used for additional testing.

Grants and scholarships to support the project from Brown, Meredith, Brilliant, and other members of the American Beethoven Society, including the purchase prices of the locks of hair acquired after 2014, total $176,000.

The following is a summary for the purpose of the grants:

May 2016: The Max Planck Institute for genome sequencing

July 2019: The Max Planck Institute for sequencing a high-coverage genome from the Stumpff lock

January 2020: For access to the UK BioBank data

March 2021: FamilyTreeDNA to test for possible close Y-chromosonal matches to the Stumpff Lock

December 2017 through March 2022: Scholarships to Tristan Begg to support his ongoing genome research and his Ph.D. research at the University of Cambridge

In 2017 the American Beethoven Society agreed that Tristan Begg would be given complete access to the results from the genome research as a basis for his Ph.D. dissertation. On January 1, 2018, Begg advised the members of the Society who have been investing in the project that he has been allowed to change his Ph.D. focus to interpreting Beethoven’s genome and integrating it with his biography.

[1] Hans Bankl and Hans Jesserer, Die Krankheiten Ludwig van Beethovens: Pathography seines Lebens und Pathologie seiner Leiden (The Illnesses of Ludwig van Beethoven: Pathography of His Life and Pathology of His Suffering) (Vienna: Verlag Wilhelm Maudrich, 1987). See specifically chapter “Knochenfragmenten aus dem Schädel Beethovens” (Fragments from the Skull of Beethoven), pp. 103-09.

[2] See Martin, Beethoven’s Hair, pp. 195, 198-204, 216.

[3] See Martin, Beethoven’s Hair, pp. 223, 234-35, 237-39.

[4] See Martin, Beethoven’s Hair, pp. 195, 216-28, 232-35, 241, 270-71.

[5] Christian Reiter, “The Causes of Beethoven’s Death and His Locks of Hair, A Forensic-Toxicological Investigation,” The Beethoven Journal 22, no. 1 (2007): 2-5.

[6] Mount Sinai press release: “Beethoven Unlikely to Have Died from Lead Exposure” (New York, June 2, 2010); James Barron, “Beethoven May Not Have Died of Lead Poisoning, After All,” New York Times (May 28, 2010).

[7] Josef Eisinger, “Was Beethoven Lead-Poisoned?” The Beethoven Journal 23, no. 1 (Summer 2008): 15-17.

[8] William Meredith, “The History of Beethoven’s Skull Fragments: Part One,” The Beethoven Journal 20, nos. 1-2 (Summer and Winter 2005): 1-25.

[9] Meredith, “The History of ‘Beethoven’s’ Skull Fragments: Part Two,” The Beethoven Journal 30, no. 1 (2015): 25-29.