2014-2023

March 22, 2023: Ludwig van Beethoven’s genome has been sequenced for the first time by an international team of thirty-two scientists using five genetically matching locks of the well-known composer’s hair. The lead author is Tristan Begg, doctoral candidate at Cambridge University. Research published in Current Biology shows that DNA from five locks of hair —all dating from the last seven years of Beethoven’s life—originate from a single individual matching the composer’s documented ancestry. By combining genetic data with closely examined provenance histories, researchers conclude these five locks are “almost certainly authentic.”

TJA Begg et al., “Genomic Analyses of Hair from Ludwig van Beethoven,” Current Biology (March 23, 2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.041

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(23)00181-1

To see selected articles and other media about the paper, see the links in Beethoven Scholars in the News.

The research, led by the University of Cambridge; the Ira F. Beethoven Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University, and the American Beethoven Society; KU Leuven; FamilyTreeDNA; the University Hospital Bonn and the University of Bonn; the Beethoven-Haus, Bonn; and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, uncovers important information about the composer’s health and poses new questions about his recent ancestry and cause of death.

On December 23, 2014, project lead Tristan Begg, who was working on his masters at the University of Tübingen and would later embark on a doctorate at Cambridge University, asked William Meredith, director of the Beethoven Center and Executive Director of the American Beethoven Society, to collaborate on the project by supplying samples from the Center’s collection of locks of hair, including the Hiller Lock that is the subject of Russell Martin’s book Beethoven’s Hair and the documentary film based on the book. William Meredith subsequently acquired additional locks for the study, as did Kevin Brown, a board member of the American Beethoven Society. Over the next eight years, the international team expanded to include thirty-two scientists and music historians. As director of the Beethoven Center, Meredith’s goals were to (1) authenticate Beethoven’s genome so that only authentic locks of hair would be on display in centers and museums around the world, and (2) to discover whatever could be found about the composer’s health through his genome.

The study’s primary aim is to shed light on Beethoven’s health problems, which famously include progressive hearing loss, beginning in his mid- to late-20s and eventually leading to him being functionally deaf by 1818. The team also investigated possible genetic causes of Beethoven’s chronic gastrointestinal complaints, and a severe liver disease that culminated in his death in 1827.

Beginning in his Bonn years, the composer suffered from “wretched” gastrointestinal problems, which continued and worsened in Vienna. In the summer of 1821, Beethoven had the first of at least two attacks of jaundice, a symptom of liver disease. Cirrhosis has long been viewed as the most likely cause of his death at age 56.

Beethoven had requested in a document written on October 6th and 10th, 1802 known as the Heiligenstadt Testament that his illness be described, and that this description be made public: “as soon as I am dead and if Professor Schmid[t] is still alive, then ask him in my name, to describe my disease [Krankheit], and attach this here-written pages of the history of my disease, to thereby at the least the world will be reconciled with me after my death as much as possible—” (translation William Meredith). (By “my disease” Beethoven meant his deafness, which almost caused him to commit suicide: “only a little [more] was missing, and I would have ended my life—”)

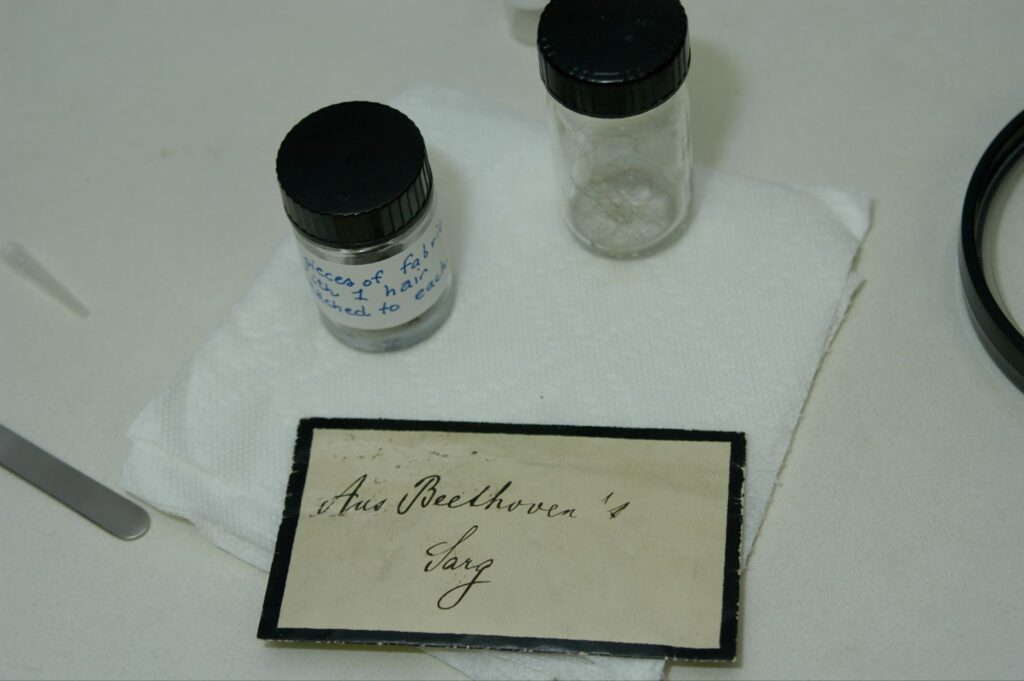

The team was able to sequence Beethoven’s genome by adapting ancient DNA techniques originally developed to sequence DNA from prehistoric human remains to the analysis of historical hair samples, which enabled the reconstruction of the majority of Beethoven’s genome using small quantities of his hair. The team report that DNA from five out of eight analyzed locks, which span roughly the last seven years of the composer’s life, match the ancestry and antiquity expected for Beethoven. Six of the tested locks belonged to the Beethoven Center or a member of the board of the American Beethoven Society; one belonged to the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign; and one belonged to the Beethoven-Haus, Bonn. In combination with analyses of their provenance histories, they claim that these five matching locks are almost certainly authentic.

Three of the five authentic locks belong to Kevin Brown, board member of the American Beethoven Society. See the section “Three Authentic Beethoven Locks” for photographs and descriptions of the provenance of those locks. The fourth authentic lock—the Schindler-Moscheles Lock—was a gift to the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies at San José State University from the American Beethoven Society. A photograph and description of it may be viewed at:

https://digitalcollections.sjsu.edu/islandora/object/islandora%3A18995

The fifth authentic lock—the Streicher-Müller Lock, belongs to the Beethoven-Haus, Bonn, and came as part of the Bodmer collection:

https://www.beethoven.de/s/catalogs?opac=bild_en.pl&t_idn=bi:i3851

Beethoven’s genome was reconstructed from the best preserved among these samples, the Stumpff Lock (owned by Kevin Brown, board member of the American Beethoven Society).

Genetic clues to Beethoven’s health

The team of scientists were unable to find a definitive cause for Beethoven’s deafness or gastrointestinal problems. However, they did discover a number of significant genetic risk factors for liver disease. They also found evidence of an infection with hepatitis B virus in at latest the months before the composer’s final illness.

Lead author, Tristan Begg, said, “We can surmise from Beethoven’s ‘conversation books,’ which he used during the last decade of his life, that his alcohol consumption was very regular, although it is difficult to estimate the volumes being consumed. While most of his contemporaries claim his consumption was moderate by early 19th century Viennese standards, there is not complete agreement among these sources, and this still likely amounted to quantities of alcohol known today to be harmful to the liver. If his alcohol consumption was sufficiently heavy over a long enough period of time, the interaction with his genetic risk factors presents one possible explanation for his cirrhosis.”

The research team also suggests that Beethoven’s hepatitis B infection might have driven the composer’s severe liver disease, exacerbated by his alcohol intake and genetic risk. However, scientists caution that the nature and timing of this infection—which would have greatly influenced its relationship with Beethoven’s liver disease—could not currently be determined, and similarly caution that the true extent of his alcohol consumption remains unknown.

Beethoven’s hearing loss has been linked to several potential causes, among them diseases with various degrees of genetic contributions. Investigation of the authenticated hair samples did not reveal a simple genetic origin of the hearing loss. Dr. Axel Schmidt at the Institute of Human Genetics at the University Hospital of Bonn, said, “Although a clear genetic underpinning for Beethoven’s hearing loss could not be identified, the scientists caution that such a scenario cannot be strictly ruled out. Reference data, which are mandatory to interpret individual genomes, are steadily improving. It is therefore possible that Beethoven’s genome will reveal hints for the cause of his hearing loss in the future.”

It proved impossible to find a genetic explanation for Beethoven’s gastrointestinal complaints, but the researchers argue that coeliac disease and lactose intolerance are highly unlikely based on the genomic data. Beethoven was also found to have a certain degree of genetic protection against risk of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), often suspected as a cause, rendering this a less likely explanation.

“We cannot say definitely what killed Beethoven, but we can now at least confirm the presence of significant heritable risk, and an infection with hepatitis B virus,” said Johannes Krause, from the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology. “We can also eliminate several other less plausible genetic causes.”

“Taken in view of the known medical history, it is highly likely that it was some combination of these three factors, including his alcohol consumption, acting in concert, but future research will have to clarify the extent to which each factor was involved,” Tristan Begg adds.

Authenticating Beethoven’s hair

In total, the team conducted authentication tests on eight hair samples acquired from public and private collections in the UK, continental Europe and the US. In doing so, the researchers discovered that at least two of the locks did not originate from Beethoven, including a famous lock once believed to have been cut from the recently deceased composer’s head by the 15-year-old musician Ferdinand Hiller.

Previous analyses of the ‘Hiller lock’ supported the suggestion that Beethoven had lead poisoning, a possible factor in his health complaints, including his hearing loss. William Meredith, who was part of a team involved in earlier scientific analyses of Beethoven’s remains and initiated the present study with Tristan Begg, said: “Since we now know that the ‘Hiller lock’ came from a woman and not Beethoven, none of the earlier analyses based solely on that lock apply to Beethoven. Future studies to test for lead, opiates, and mercury must be based on authenticated samples..”

The five samples identified as being authentic and from the same person belong to Kevin Brown (three samples); the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies in San José, California (on sample); and to the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn. Beethoven’s whole genome was sequenced from one of Brown’s samples, the ‘Stumpff Lock,’ which emerged as the best-preserved sample. The team found the strongest connection between the DNA extracted from the Stumpff lock of Beethoven’s hair and people living in present day North Rhine-Westphalia, consistent with Beethoven’s known German ancestry.

A family mystery

The team analysed the genetics of living relatives in Belgium but could not find matches among either of them. Some of them share a paternal ancestor with Beethoven in the late 1500s and early 1600s based on genealogical studies, but they did not match the Y-Chromosome found in the authentic hair samples. The team concluded that this was likely to be the result of at least one “extra-pair paternity event”—a child resulting from an extramarital relationship—in Beethoven’s direct paternal line. Genetic genealogist Maarten Larmuseau from the KU Leuven said: “Through the combination of DNA data and archival documents, we were able to observe a discrepancy between Ludwig van Beethoven’s legal and biological genealogy.”

The study suggests that this event occurred in the direct paternal line between the conception of Hendrik van Beethoven in Kampenhout, Belgium in c.1572, and the conception of Ludwig van Beethoven seven generations later in 1770, in Bonn, Germany. Although a doubt had earlier been raised concerning the paternity of Beethoven’s father owing to the absence of a baptismal record, the researchers could not determine the generation during which this event took place.

Begg said: “We hope that by making Beethoven’s genome publicly available for researchers, and perhaps adding further authenticated locks to the initial chronological series, remaining questions about his health and genealogy can someday be answered.”

Q and A about the Genome Project

(see the Beethoven-Haus website for the full set)

The director of the Beethoven-Haus, Malte Boecker, asked me to answer a few questions about the project for the BH website, which I was happy to send him. Although they duplicate information elsewhere on my website, I reproduce my answers here. I do recommend interested people consult the complete BH Q&A, as it contains other interesting questions, especially about the ethics of the project. At the moment, most of the answers to the questions are only in German.

BH: “How did the project come about? Why was it initiated?“

The unsuccessful stage of the quest for Beethoven’s genome began on December 1, 1994—the successful stage began two decades later in December 2014. On December 1, 1994, four members of the American Beethoven Society bought a lock said to be of Beethoven’s hair at Sotheby’s, London. After its arrival, a majority of the “Ferdinand Hiller Lock” and the original locket were given to the Beethoven Center. The remaining portion of the lock went to one of the four members, Dr. Alfredo Guevara, who had donated the principal amount of funding and who agreed to give strands from his share to researchers for testing. When the lock was put on display at the Center in 1996, many visitors asked how we knew it was really Beethoven and if we had had its DNA tested. In 1999 mitochondrial DNA tests were conducted by scientists at LabCorp of America, but the tests were not successful because science had not made the necessary advances in testing hair. The initial DNA tests were undertaken to (1) confirm that the Hiller Lock was actually from the composer so that it could be displayed as authentic, and (2) to help us advance our understanding of the composer’s health if the lock was authentic.

Knowing that the initial 1999 mitochondrial DNA analysis had failed, in December 2014 Tristan Begg, then a masters student in archaeological sciences at the University of Tübingen, informed Director William Meredith of the Beethoven Center that the necessary advances had been made in next generation genome sequencing and requested that the Center participate in a new quest to identify Beethoven’s genome. Dr. Guevara agreed to share strands of hair from the Hiller Lock and the Center and Kevin Brown, a member of the board of the American Beethoven Society, began to acquire other locks for testing as part of the project team.

The Hiller Lock was the first to be tested but proved to be unauthentic, which is unfortunate because tests on strands from it in 1997-98 (Walter McCrone and William Walsh) and 2007 (Christian Reiter) had indicated that the composer suffered from lead poisoning.

Though the Hiller Lock was probably authentic originally—Ferdinand Hiller visited Beethoven with his teacher Hummel on four occasions when he was alive as well as the day after the composer’s death—some type of accident subsequently occurred before 1911 that apparently destroyed the original lock and inscription while it was owned by Hiller’s son Paul, who had received it in 1883. A lock of hair from a Jewish woman (perhaps Paul’s wife Sophie Lion) was put in the locket as replacement with a newly copied transcription. The new genome research in 2016 confirmed that (1) the Hiller lock was not authentic and should not be displayed, and (2) any results from testing strands from that lock did not relate to Beethoven.

Fortunately, five authentic matching samples were discovered as part of the post-2014 genome research, three currently belonging to Kevin Brown, a board member of the American Beethoven Society, acquired for the genome project; one from the Beethoven Center; and one from the Beethoven-Haus. The authentication of the genome in five different locks now allows museums to display authentic locks with confidence once they are tested. The project has also discovered previously important unknown information about the composer’s genetic and medical history, more than meeting the initial second goal.

BH: “How long did the project take to complete?“

After the initial agreement between Tristan Begg and the Beethoven Center was made in December 2014, the project took eight years to complete as it succeeded in identifying the five authentic locks and subsequently conducted deep analysis of the best-preserved lock (the Stumpff Lock, owned by Kevin Brown, the board member of the American Beethoven Society who acquired it at a Sotheby’s, London auction in 2016.) Thirty additional experts joined the team over the seven years of the project that resulted in the final paper. The contributions of this total team of thirty-two experts were essential for the breadth of the findings.

BH: “How much did the investigation cost? How was it financed?“

The investigation cost $176,000 in direct funding from members of the American Beethoven Society as well as in-kind support from the University of Tuebingen, the Max Planck Institute, and Cambridge University. The direct funding was used to acquire seven locks, four of which proved to be authentic (three belonging to board member Kevin Brown, one to the Center), two that were not authentic (the Hiller Lock owned by the Center and the Cramolini Lock owned by the Society), and one that was not tested because of the fragility of the object (the Betty Hummel Lock owned by the Center). Additional funding was contributed for the project to help cover costs of testing the locks and for scholarship support for the research undertaken by Tristan Begg at Cambridge University. The research conducted at the laboratories at the University of Tuebingen and Max Planck Institute made the project a possibility.

The press release mentions a previous scientific study on the lead content of Beethoven’s hair. Which study is that, and which of its statements have now been refuted by the present project?

In 2007 then head of the Department of Forensic Medicine in the Medical University of Vienna Dr. Christian Reiter published an article in The Beethoven Journal on his research on strands of hair that were said to be from Beethoven (“The Causes of Beethoven’s Death and His Locks of Hair: A Forensic-Toxicological Investigation”). Dr. Guevara agreed to give Dr. Reiter two strands of hair from the Hiller Lock. Dr. Reiter’s spectrometric analyses discovered that “several phase of elevated lead content appeared” that he related to the four paracenteses were ordered to be performed by Beethoven’s doctor. Dr. Reiter concluded that Dr. Wawruch, “had nevertheless thereby caused Beethoven’s death.” Dr. Reiter subsequently tested a strand of hair from a lock at the Beethoven Memorial Site in Jedlersee that lacks provenance: “… the results were essentially in agreement for the last 111 days of Beethoven’s life, … which provides confirmation of the initially assumed authenticity of this lock.” He also tested strands from a lock from Anton Halm: “The pattern of its heavy metal distribution was found to be congruent with the pattern characteristic of Beethoven’s discovered in the Guevara and Erdödy locks.” The genome paper’s finding that the Hiller Lock is inauthentic means that the results from those two strands do not relate to Beethoven.

BH: “Our team thinks that these are the relevant studies that are now considered obsolete, could you kindly specify?“

Russell Martin, Beethoven’s Hair, New York: Broadway Books, 2000.

Russell Martin chronicled the fascinating history of the Hiller Lock as he could construct it through 1999 when the book went to press. His book ends by announcing that attempts were being made to match DNA from the Hiller Lock with that of fragments supposedly from Beethoven’s skull with the hope that “both hair and bone had come from the same person.” He concludes, “finally it would be certain beyond any doubt that the treasured lock that had made that improbable journey and along the way transformed so many lives was, quite wonderfully, Beethoven’s hair.” Martin’s book remains a valuable recounting of the history of the lock through its role in the attempted rescue of the Danish Jews, but it now requires a new updated conclusion. With the 2016 discovery that the Hiller Lock was replaced with the lock from the hair of a Jewish woman and probably while the hair was still in the possession of Paul Hiller, the lock’s history becomes even more complex and interesting. The discovery also allows Martin to continue the investigation into the replacement by contacting members of the family of Paul Hiller’s wife, Sophie Lion, who moved to Brazil in the 1930s to escape the Nazis, to try to match the DNA.

Concerning the list below sent to me by the Beethoven-Haus, any results obtained solely from strands of the Hiller Lock do not pertain to Beethoven.

Christian Reiter, “The Causes of Beethoven’s Death and His Locks of Hair: A Forensic-Toxicological Investigation,” The Beethoven Journal 22, no. 1 (2007): 2–5.

Christian Reiter, “Beethovens Todesursachen und seine Locken. Eine forensisch-toxikologische Recherche,” Mitteilungsblatt der Wiener Beethoven-Gesellschaft 38 (2007): 1–6.

Josef Eisinger, “The Lead in Beethoven’s Hair,” Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry 90, no. 1-2 (2008): 1–5.

Josef Eisinger, “Was Beethoven Lead-Poisoned?,” The Beethoven Journal 23, no. 1 (2008): 15–17.

Manfred Gross, “Beethovens Locken – medizinisch betrachtet,” Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 138 (2013), S. 2633–2638.

Michael H. Stevens, Teemarie Jacobsen, and Alicia Kay Crofts, “Lead and the Deafness of Ludwig van Beethoven,” The Laryngoscope 123 (2013): 2854–2858.

People and Timeline

Tristan Begg was tasked with numerous responsibilities for The Beethoven Genome Project, beginning with laboratory testing in 2015 of recently developed ancient DNA methods using ancient and historical locks of hair, in order to establish the material and economic feasibility of sequencing a high-coverage genome from small quantities of Beethoven’s hair. Between 2015 and 2020, Tristan performed authentication testing on eight locks of hair attributed to Beethoven, discovering that five originated from Beethoven. He additionally discovered in 2016 that the Hiller Lock originated from a woman. In May of 2019, using a low-coverage draft genome paired with a recently developed low-coverage imputation method, Tristan first identified significant genetic risk factors for liver disease in interaction with alcohol consumption in Beethoven’s PNPLA3 and HFE genes, a finding he later confirmed in his analysis of Beethoven’s high-coverage genome in November of 2019. Also in November of 2019, Tristan discovered an extra-pair paternity event in Beethoven’s direct patrilineage. Tristan’s additional responsibilities for the Current Biology paper Genomic analyses of locks of hair from Ludwig van Beethoven included retrospective cohort analyses, polygenic risk scoring, sex determination, autosomal and mitochondrial relatedness-testing between Beethoven hair samples, pedigree simulations, and PCA and ADMIXTURE ancestry analyses, as well as reconstructing sample provenance histories with William Meredith, applying for the UK BioBank dataset with Dr. Robert Attenborough, and acquiring funding for the sequencing of the five living Van Beethovens.

https://photos.app.goo.gl/EGAPdtorKp1u7xNKA

https://photos.app.goo.gl/ZpBbH8SvX3hr2c7TA

Dr. Arthur Kocher, a post-doc of Dr. Denise Kuhnert and Prof. Dr. Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, first detected hepatitis B virus (HBV) reads in shotgun-sequence data from the Stumpff Lock in May of 2019, later confirming an HBV infection through targeted-capture for HBV DNA. All HBV analyses were concluded in June of 2021.

By March of 2019 Prof. Dr. Maarten H. D. Larmuseau of KU Leuven located and acquired saliva samples from five living patrilineal relatives of Beethoven, who are documented as sharing a common patrilineal ancestor with Beethoven in Aert van Beethoven. Dr. Larmuseau additionally assisted Dr. John Wilson (Austrian Academy of Sciences) in locating the living genealogical descendants of Beethoven’s nephew, Karl van Beethoven.

In February of 2020, in an effort to better interpret the discovery of an extra-pair paternity event in Beethoven’s patrilineage, FamilyTreeDNA were approached in order to query their large and genealogically explicit Y-chromosomal database for possible close matches to Beethoven’s Y-chromosome. Drs. Goran Runfeldt and Paul Andrew Maier of FamilyTreeDNA recruited several potential distant Y-chromosomal relatives of Beethoven identified within their database for deeper sequencing, and, with the aid of Dr. Michael Sager, discovered the novel I-FT396000 Y-haplogroup in which Beethoven and five of these distant relatives belong (as of January, 2023). In addition, Drs. Runfeldt and Maier first detected the lack of IBD-sharing between Beethoven and three living genealogical descendants of Karl van Beethoven in May of 2021, and introduced the novel local ancestry determination method, Geogenetic-Triangulation (GGT), finding that most of Beethoven’s ancestor’s likely originated in Germany.

Dr. Axel Schmidt at the University of Bonn performed Variant Effect Predictor analyses on a list of genes he collated, in which deleterious variants may have been causal to monogenic forms of diseases Beethoven may have suffered from. Dr. Schmidt additionally assessed the coverages of these genes. All medical genetic analyses were performed under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Markus Nöthen, also at the University of Bonn.

Dr. Kay Prüfer, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, performed mapping and genotyping of Beethoven’s high-coverage genome, additionally generating the accessibility filter for ultra-short-reads. Dr. András Szolek of the University of Tübingen and Dr. Rodrigo Barquera of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology determined Beethoven’s HLA genotypes.

Tristan Begg was born in Leeds, England, in 1990, and grew up in the San Francisco Bay area from 1995 to 2013. His earned his undergraduate degree at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in Physical Anthropology in 2012 with a minor in European history, and a masters of science degree in Archaeological Sciences: Paleogenetics from the University of Tuebingen in 2016. His masters thesis was advised by Johannes Krause and William Meredith. In 2023 he will complete his PhD in Biological Anthropology, from Clare Hall, Cambridge University with a dissertation on Beethoven’s genome. His dissertation advisors are Robert Attenborough, Cambridge University, and Toomas Kivisid, Katholieke Universiteit, Leuven. Tristan’s background is predominately in human skeletal biology, archaeology, and ancient DNA, and he has performed archaeological and paleoanthropological fieldwork at sites in Kenya, Germany, California, and England. In 2014 Tristan began working on The Beethoven Genome Project for his master’s thesis while studying paleogenetics at the University of Tuebingen. Tristan’s favorite hobbies and interests include history, woodworking, car and motorcycle restoration, and playing a variety of musical instruments, including bagpipe, guitar, piano, violin and viola, among others. He has been an avid listener of Beethoven’s music since 2007 and volunteered for the American Beethoven Society in 2009 as a docent for the “Schulz’s Beethoven, Schroeder’s Muse” exhibit at the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies. His email address is: TristanJ.A.Begg@gmail.com